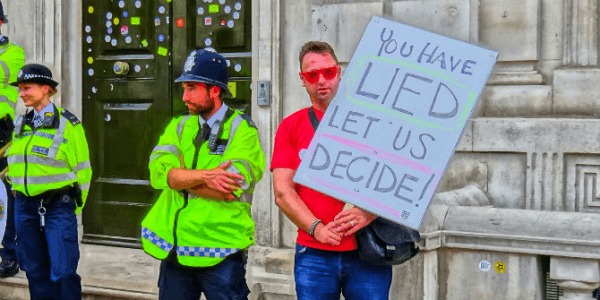

Protesters at the March for a People’s Vote, June 2018. Photo: David Holt via a CC BY 2.0 licence

Phil Syrpis, Professor of EU Law, University of Bristol Law School

Momentum seems to be building for a people’s vote on Brexit. Phil Syrpis (University of Bristol) argues that it will not provide the answer to Brexit – whether or not the government secures a deal with the EU. Rather, he argues that the calls for a people’s vote are distracting campaigners from making the case for the outcomes they really want.Numerous people and bodies have called for a people’s vote. Scratch a little below the surface, and it becomes apparent that many of these are either uncertain, or perhaps deliberately vague, about the circumstances in which it should be held.

They are also uncertain – or again perhaps deliberately vague – about the nature of the question to be put, the timing, and indeed the consequences which should flow from such a vote. As the Leave campaign can testify, there are pros and cons for groups who take this sort of stance. A vague plan might elicit support from a wide range of people. But then, it might turn out not to be able to deliver what the people were hoping for.

Calls for a people’s vote come from a variety of sources. The most enthusiastic are Remainers. They tend to see a vote as an opportunity – perhaps the last opportunity – to stop Brexit, and to enable the public to vote not, as in June 2016, on the abstract idea of leave, but instead on the government’s concrete Brexit plans. They are confident that while there was a small majority for Brexit in 2016, there would not, given what we now know, be a majority for any of the government’s possible plans – or indeed for a ‘no deal’ Brexit. Recent polls support their claim. They have been joined by a number of other groups, who argue that there is tactical political advantage to be gained (e.g. for the government and the Labour Party) in backing a people’s vote.

As we all know, Article 50 was triggered in March 2017. In the absence of an agreement with the EU, the UK will, by operation of law, crash out of the EU with no deal in March 2019. If a withdrawal agreement is reached, we seem destined for a transition period, lasting until at least December 2020. There will be a non-binding political declaration on the future relationship accompanying the withdrawal agreement; but it is likely to be very vague. This is a first problem for the people’s vote campaign. It does not seem likely that we will have a clear sense of what our future relationship with the EU will look like at the time the people are asked to vote. The claim that ‘this time, we will at least know what we are voting for’ rings hollow.

The key question to be settled by November, presumably well ahead of any possible vote, is whether Theresa May’s government will be able to reach agreement with the EU on the terms of the UK’s withdrawal. There are a number of possibilities.

Let us first assume that there is an agreement with the EU. The EU (Withdrawal) Act provides that it must then be endorsed in Parliament. Campaigners have argued for a people’s vote in this scenario; some, on the assumption that the deal is endorsed by Parliament, others, on the assumption that it is not. The question to be put to the people is whether or not to approve the deal. For some, the alternative is to leave without a deal. For others, it is reverting to EU membership. A three-option vote is possible, but brings many complications. The political stakes associated with the framing of the question in this scenario would be huge.

In the alternative, let us assume that there is ‘no deal’. Here again, we might see a people’s vote. In this case, there will of course be no deal to vote on. The binary choice would appear to be between ‘no deal’ and revoking the Article 50 notification.

What complicates things further is the fact that legislation is needed in order to provide for a people’s vote. Whatever the rights and wrongs of the idea, my claim is that Parliament is extremely unlikely, in any of the above scenarios, to endorse it.

Let’s assume again that there is a withdrawal agreement with the EU, and that Parliament endorses the deal. Why would it then call for a people’s vote? There is no reason for the government, and its supporters, to put the successful deal to a vote. And I can’t see how the parliamentary minority opposed to the deal, which wishes to challenge the deal, could overcome the arithmetic, and succeed in passing the legislation which would be necessary to put the deal to a popular vote. The call for a vote seems to rely on there being a number of MPs who are prepared to endorse a deal subject to a people’s vote, which they would not be prepared to endorse without one. That position is possible, but I doubt many MPs subscribe to it. In this case, my conclusion is that, very much against the odds, the government’s political Brexit strategy will have been a success. The will of Parliament would simply be done.

If, in the alternative, Parliament rejects the government’s deal, we would be in a very different place. We would, in fact, be in much the same place as we would be in if the government was not able to reach a deal with the EU. In both these cases, the government would have failed in its Brexit mission to reach an agreement with the EU and to get it through Parliament. The ERG wing of the Conservative Party would, presumably, urge May towards ‘no deal’ (or perhaps, towards a ‘harder’ version of the Brexit deal articulated by the government). The Labour Party would, presumably, call for a general election. They may, together with some Conservatives, try to articulate a ‘softer’ Brexit deal, which, they might argue, would be accepted by Parliament and the EU. And there are some – perhaps many – within both main parties who would join with the smaller parties (and incidentally, with me) to argue that, as Brexit will have failed, we should revoke the Article 50 notification and remain within the EU.

Would this be fertile ground for a people’s vote? I find it difficult to see why a majority in Parliament would be prepared to put the ‘failed deal’ to the popular vote. For that to happen, it would need the support of a number of MPs who have rejected the deal, but who would ultimately be prepared to accept it if it proved to have sufficient popular support. Again, this position is possible in theory, but not likely in practice. It is, I think, more likely that the ‘failed deal’ would not be put to the public. Thus the choice to be put to the people would be ‘no deal’ or remain. But it is far from clear that this political scenario can, or should, be reduced to that binary question. More than that, it is unlikely that Parliament would choose to put that binary question to the people. There would be intense pressure to seek to find a ‘better deal’, and various calls for both a Conservative Party leadership election and a general election.

Thus, in each of the scenarios considered above – a deal endorsed by Parliament, a deal rejected by Parliament, or no deal with the EU – it is unlikely that the people’s vote will either be called upon, or needed, to solve the Brexit riddle.

The core problem – which the people’s vote does not address – is that the rival groups (the government, the ERG and the Labour Party, among others) have yet to set out their Brexit visions. Calls for a vote are a dangerous distraction from the urgent task of preparing alternatives to ‘no deal’.

Those who wish to remain should be making the case for remain – arguing that the government’s failure to reach a deal with the EU which attracts Parliamentary support represents a failure of Brexit, and therefore demands an end to the Article 50 withdrawal process. That case can and should be made without the need for a people’s vote.

Article originally published in the LSE blog. Reproduced with kind permission.

Article originally published in the LSE blog. Reproduced with kind permission.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the Brexit blog, nor the LSE.

Phil Syrpis is Professor of EU Law at the University of Bristol. He researches EU social and internal market law, and, since 2016, Brexit. His inaugural lecture, delivered in May 2018, discusses the impact which Brexit has had on EU law scholarship. It is available here.