The British Home Office has created a bureaucratic nightmare for EU citizens applying for permanent residency. Might there be a better way forward?

According to official figures there are over three million non-UK EU citizens living in the United Kingdom, many of which live in Bristol. Following the referendum of 23 June 2016 and the notification by the UK government to withdraw from the European Union many of those citizens are naturally feeling anxious about Brexit and the future of their rights in this country. What will happen to them once the UK leaves the EU is still unclear. In the Guidelines Following the UK’s Notification under Article 50 TEU adopted on 29 April 2017, the EU 27 recognise that “the United Kingdom’s decision to leave the Union creates significant uncertainties that have the potential to cause disruption”, notably for “[c]itizens who have built their lives on the basis of rights flowing from the British membership of the EU [and] face the prospect of losing those rights”.

According to official figures there are over three million non-UK EU citizens living in the United Kingdom, many of which live in Bristol. Following the referendum of 23 June 2016 and the notification by the UK government to withdraw from the European Union many of those citizens are naturally feeling anxious about Brexit and the future of their rights in this country. What will happen to them once the UK leaves the EU is still unclear. In the Guidelines Following the UK’s Notification under Article 50 TEU adopted on 29 April 2017, the EU 27 recognise that “the United Kingdom’s decision to leave the Union creates significant uncertainties that have the potential to cause disruption”, notably for “[c]itizens who have built their lives on the basis of rights flowing from the British membership of the EU [and] face the prospect of losing those rights”.

Clarifying the status of EU citizens could have been done unilaterally by the British government. It chose not to, however, arguing that the status of UK nationals in EU states also needed to be addressed and reciprocal rights offered. Although the issue was raised in parliament during the debate over the European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Bill legal uncertainty remains. The European Union has on several occasions stressed that finding a solution to this issue was paramount and needed to be tackled at an early stage of the Brexit negotiations. Indeed as stressed in paragraph eight of the EU 27’s guidelines, “[t]he right for every EU citizen, and of his or her family members, to live, to work or to study in any EU Member State is a fundamental aspect of the European Union”.

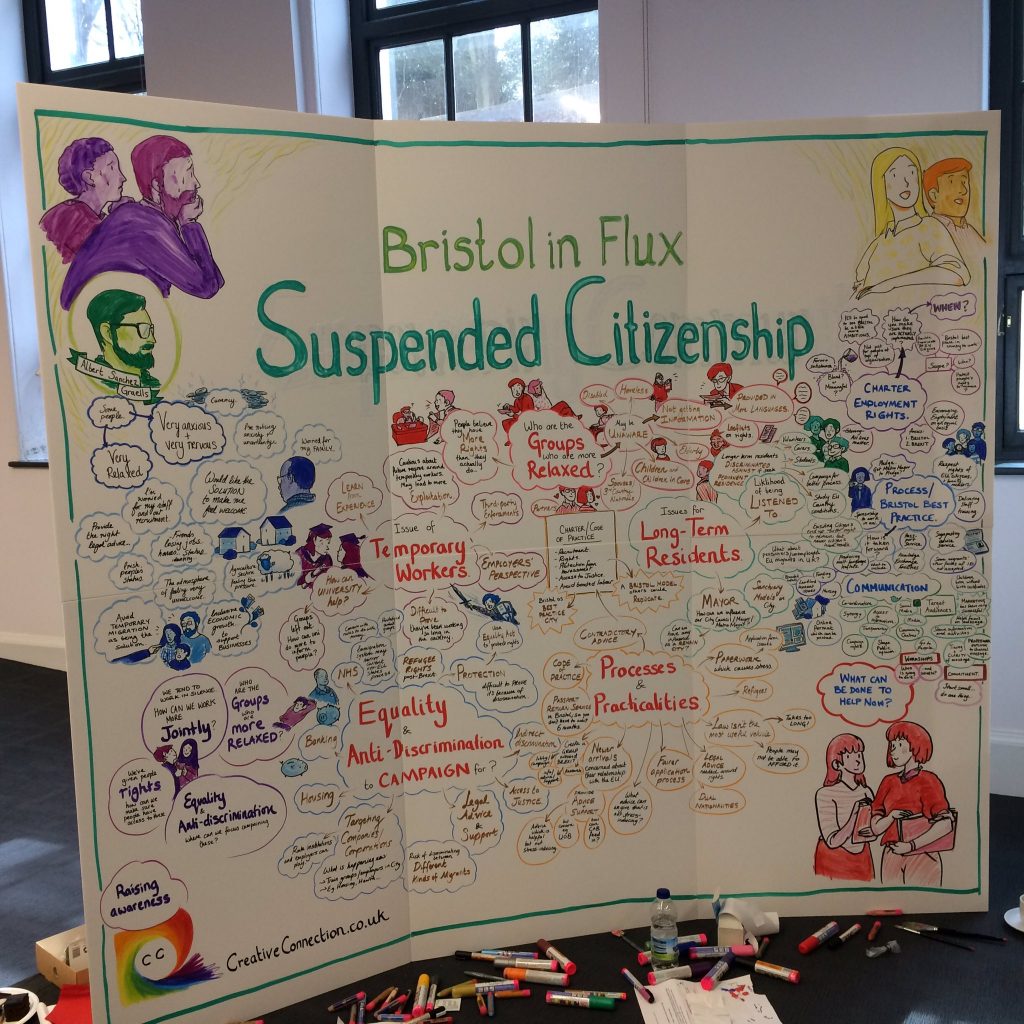

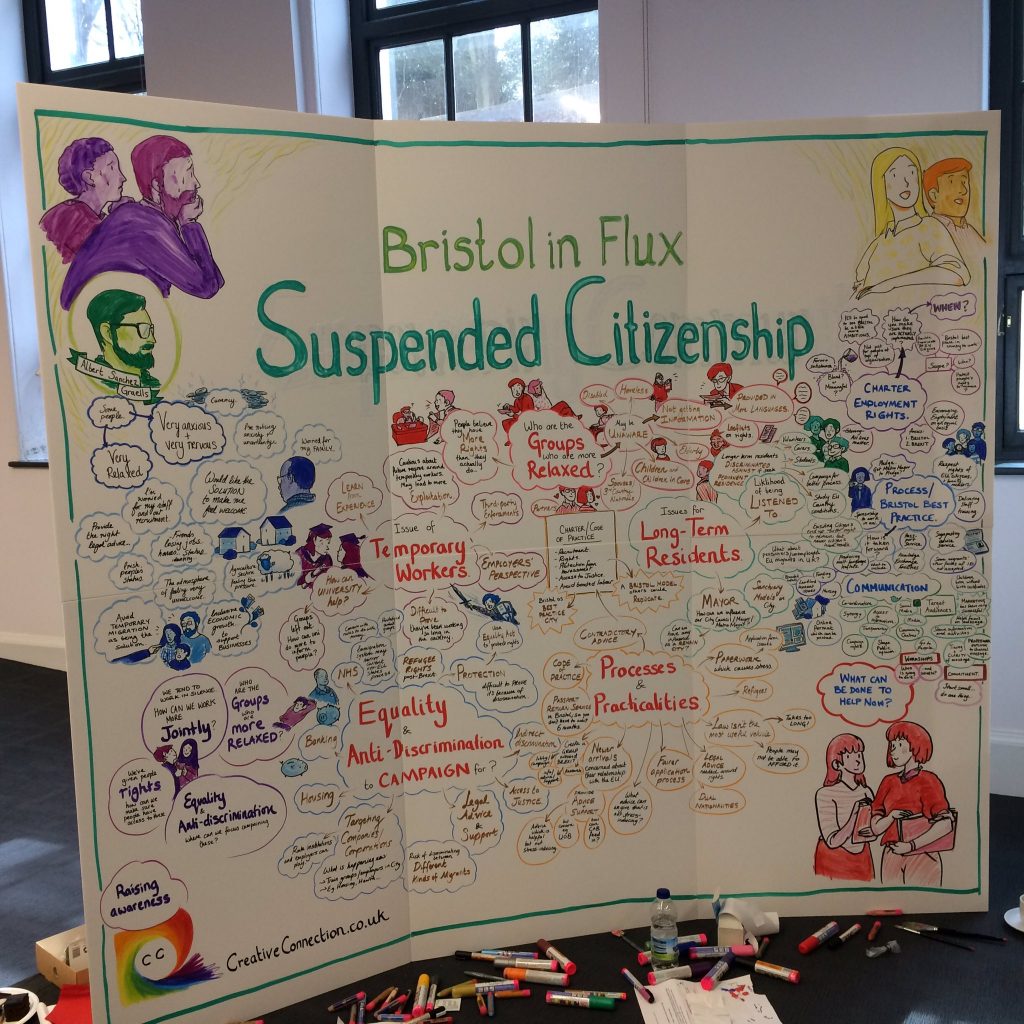

This was the main theme of the workshop ‘Bristol in Flux: Suspended Citizenship’ organised by the University of Bristol on 3 April 2017 to which we, as lecturers in EU Law at the University of the West of England and authors of the textbook European Union Law, were invited. One of the subtopics broached at the workshop was the fate of long-term EU residents who seem to be most affected by Brexit. The debate predominantly centred upon two themes of immediate practical relevance: first, the conditions for obtaining a UK status, and second, the processes and practicalities of transforming their EU status into a UK status. Continue reading →

The following is a record of the findings of the panels speaking at an event held on 4 October 2017. The first panel (Clair Gammage, Maria Garcia and Tonia Novitz, chaired by Phil Syrpis) examined the external policies of the European Union (EU) particularly in the context of regionalism and free trade agreements (FTAs). The second panel (Emily Jones, Sophie Hardefeldt and Gabriel Siles-Brügge, chaired by Tonia Novitz) examined how the UK could – in the event of Brexit – depart from or improve on the practices of the EU.

The following is a record of the findings of the panels speaking at an event held on 4 October 2017. The first panel (Clair Gammage, Maria Garcia and Tonia Novitz, chaired by Phil Syrpis) examined the external policies of the European Union (EU) particularly in the context of regionalism and free trade agreements (FTAs). The second panel (Emily Jones, Sophie Hardefeldt and Gabriel Siles-Brügge, chaired by Tonia Novitz) examined how the UK could – in the event of Brexit – depart from or improve on the practices of the EU.

According to

According to