Bristol strongly supported Remain but not all of its component parts did. Ward-level data reveals who voted for what, why, and thus how we might move forward as a community.

Figure 1 How Bristol voted in the EU referendum, ward by ward, with a high Remain vote in red and a low Remain vote in yellow. The original interactive map can be found on Bristol247.com who kindly gave us permission to use this image.

At odds with much of England, the City of Bristol voted overwhelmingly for Remain in the EU referendum, with 62% as opposed to 38% for Leave. Hundreds marched through the centre of Bristol to show their dismay the day after the referendum result. At the same time, recently available ward level data indicates the outer areas of Bristol including Bishopsworth, Hartcliffe and Hengrove were majority Leave. Just as a picture of a deeply divided country emerged on 24 June 2016, can we understand Bristol as a microcosm of modern Britain? And what exactly does it mean to vote Leave in a city which was enthusiastically Remain?

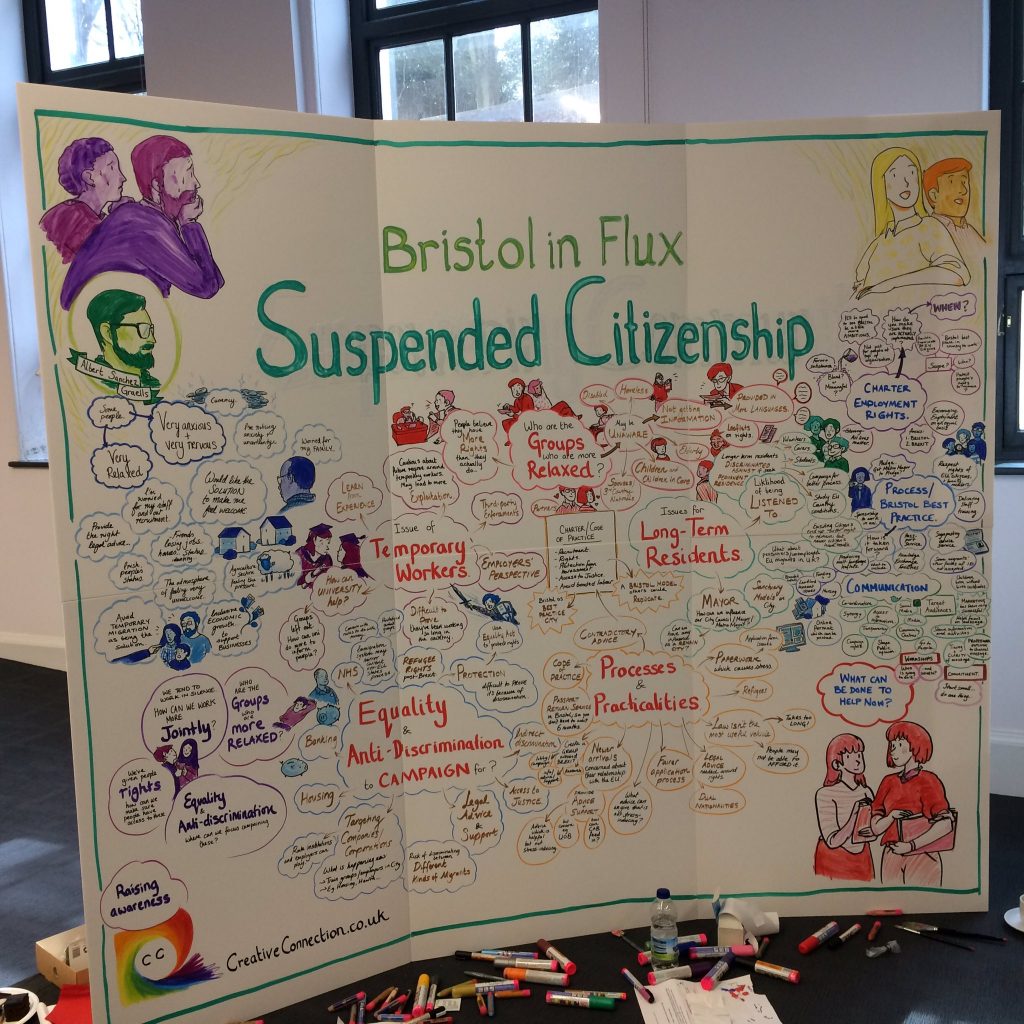

On 4 April 2017, the University of Bristol hosted a workshop on local communities as part of the wider initiative ‘#BristolBrexit – A City Responds to Brexit’. Working closely with local residents, city officials, stakeholders, practitioners and charities in Bristol, the workshop sought to include a balance of participants between central Bristol and the outer estates. The workshop participants identified the challenges we face post-Brexit with a particular focus on Bristol, including the racism and prejudice faced by minority communities, ensuring the rights of EU citizens in the UK, and the general sense of insecurity and uncertainty brought on by the Referendum result. Built into the design of the workshop, the conversation then turned to ‘who is missing?’. Large segments of our local communities, including young people, abstainers, and Brexiteers are still missing from the Bristol-Brexit discussion. Continue reading

According to

According to