Image: EPA-EFE/Andy Rain

Image: EPA-EFE/Andy Rain

Katy Hayward, Queen’s University Belfast; Adrienne Yong, City, University of London; Maria Garcia, University of Bath; Michael Gordon, University of Liverpool; Nauro Campos, Brunel University London, and Phil Syrpis, University of Bristol

A draft agreement on the UK’s withdrawal from the European Union has been reached between representatives of both sides, alongside an Outline Political Declaration on a future relationship. It remains to be seen whether the British government is able to survive, and gain parliamentary support for the deal. Here, though, academic experts consider what adoption of the 585-page draft Withdrawal Agreement would mean.

Northern Ireland

Katy Hayward, Reader in Sociology, Queen’s University Belfast

The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) has clearly had a powerful influence on the UK’s negotiating position over the past few months. The revised Withdrawal Agreement text reveals an extraordinary effort to allay the concerns of unionists in Northern Ireland. This effort is not merely tokenistic. Most notably, it entails a major shift from the EU side to allow the inclusion of an all-UK-EU customs arrangement as a legally secure backstop. The text says that the backstop will only kick in if a future permanent agreement that avoids a hard border on the island of Ireland can’t be secured.

The scenario in which, at the end of the transition period scheduled to end in December 2020, the UK stays in a customs union with the EU is outlined in the text’s Protocol on Northern Ireland/Ireland. Its primary purpose, therefore, is to avoid a hard border on the island of Ireland. But by making this an all-UK arrangement in order to avoid checks “in the Irish Sea”, Theresa May has risked the wrath of the hardline Brexiteers in her own party.

Read more:

Brexit backstop: this is why it’s so hard to talk about a Northern Ireland deal

As part of the backstop, the protocol does allow for a minimal level of regulatory harmonisation between Northern Ireland and the EU necessary for the free movement of goods across the Irish border. This is stressed to be envisaged as a temporary arrangement, involving a small fraction of the EU rules that currently apply in Northern Ireland. But the DUP may well believe that its blood-red lines have been drawn too thickly to allow this. After achieving so much, the DUP’s stance and determination to vote down the deal in parliament could yet compound the risk of a no-deal scenario of the UK, the most disastrous effects of which would be felt in Northern Ireland.

The Irish border – much more complicated than it looks. Paul McErlane/EPA

The Irish border – much more complicated than it looks. Paul McErlane/EPA

Parliamentary process and sovereignty

Michael Gordon, Professor of Constitutional Law, University of Liverpool

Parliamentary approval for the deal is a legally required part of the ratification process. This follows the EU (Withdrawal) Act 2018 which stipulates that parliament must have a “meaningful vote” on the deal. The House of Commons, in particular, must now positively approve the lengthy, technical Withdrawal Agreement, as well as the shorter, and much more vague, political declaration concerning the future UK-EU relationship.

This debate in the Commons will provide a forum for different lines of critique of the draft deal, and the consequences of rejection are not clear. For while different groups of MPs may object to the terms of the deal in similar ways – a common theme so far being the UK’s loss of influence over the EU rules it must accept in the transition period and perhaps beyond – there is no prospect of agreement about an alternative to the PM’s attempted compromise.

Read more:

What happens if parliament rejects a Brexit deal?

Some MPs may reject this deal in favour of no deal at all. Others want a further referendum with the option to remain in the EU. Others want a general election and a change of government. In principle, all of these options remain open if the Commons voted against the deal. But it is not clear which (if any) can attract majority support – or whether there is sufficient time (without extending negotiations) for new national votes, before March 29, 2019.

A particular point of legal controversy likely to be discussed in parliament relates to the “backstop”, which serves as a potential bridge from the transition to Britain’s future relationship with the EU. This could see the UK enter a “single customs territory” with the EU, and remain subject to aspects of EU law, without a unilateral exit clause for the UK.

Critics say this interferes with the sovereignty of parliament. But, to me, this is misguided. As a matter of domestic law, the UK parliament could always act outside the proposed review procedure, which makes any decision to end the backstop arrangements a joint matter to be decided with the EU. But if the UK did act unilaterally, it would have to accept significant international consequences, and almost certainly lose any chance at negotiating a future free trade agreement with the EU. That would be an expensive choice to make, but in this sense parliament should not see the backstop as a limit on its legal sovereignty.

The transition

Phil Syrpis, Professor of EU Law, University of Bristol

In legal terms, the Draft Withdrawal Agreement is quite an achievement. It enables the UK to leave the EU, while at the same time preserving some – but not all – the advantages of EU membership. The overall structure is as follows. First, the UK enters into a period of transition, during which a) the UK will not participate in the governance of the EU, and b) EU law will remain applicable in the UK.

Transition ends on December 31 2020, though the Joint Committee – co-chaired by the UK and European Union to oversee the withdrawal process – may “adopt a single decision extending the transition period up to [31 December 20XX]”. Next, with both parties alert to the fact that the Withdrawal Agreement cannot establish a permanent future relationship, there are complex provisions on the so-called Irish backstop. These provisions are, as the EU made clear throughout, to apply “unless and until” they are superseded by subsequent agreement.

These provisions establish “a single customs territory” between the EU and the UK, including a number of “level playing field” commitments, which will, while the backstop is in place, limit the UK’s ability to diverge from EU standards.

Finally, the Outline Political Declaration expresses the (non-legally binding) intention to replace the backstop with an agreement which ensures the absence of a hard border on the island of Ireland. To the extent that the Withdrawal Agreement refers to union law, it is to be interpreted in accordance with the case law of the Court of Justice of the European Union.

Time will tell how this compromise solution, similar in many ways to the EU’s current relationships with Turkey and the Ukraine, will be assessed. I rather feel that there may be too much entanglement with the EU here for Brexiters to swallow; and too much of a step down from single market membership to satisfy Remainers.

What it means for citizens

Adrienne Yong, Lecturer at The City Law School, City, University of London

The text of Part Two on Citizens’ Rights in this version of the Draft Withdrawal Agreement is largely replicated from the version published in March 2018. This is unsurprising given that the UK and EU indicated in March that EU citizens’ rights was one of the few things that were agreed upon by both parties early on. As such, there are few surprises on this front.

The main point to highlight is that the rights to reside, entry and exit for EU citizens and their families largely derived from the Citizens’ Rights Directive 2004/38. If an EU citizen has not yet lived in the member state for the five years needed to get permanent residency, or arrives during the transition period (after March 29, 2019 and before December 31, 2020), then the agreement allows them the right to reside, assumedly subject to the rules under the EU’s settlement scheme. Children born after the UK’s withdrawal are also protected.

What is still unclear is whether those known as “Zambrano carers” of British citizens, namely citizens from outside the UK who care for British citizens and who they depend on, are covered by the agreement. It may well become a case-by-case analysis of whether they fall under the definition of a “family member” under Article 9 of the Draft Withdrawal Agreement.

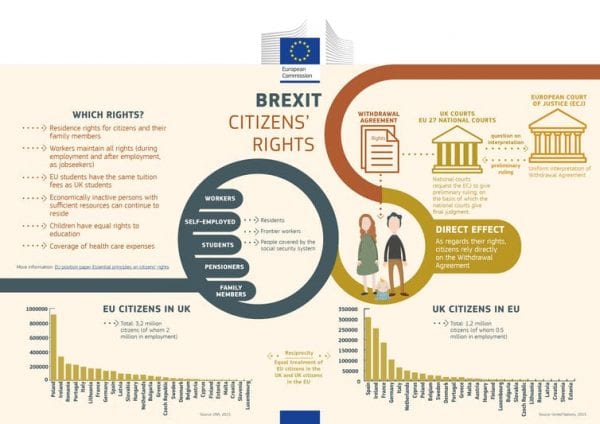

What Brexit means for citizens’ rights. European Commission

What Brexit means for citizens’ rights. European Commission

What it means for the UK economy

Nauro Campos, Professor of Economics, Brunel University London

The draft Withdrawal Agreement would guarantee a transition period during which the UK economic relationship with the EU remains unchanged. A no-deal, disorderly exit will be avoided, at least until the end of the transition period.

Business will very much welcome this. It means it will not have to spend resources trying to minimise the severe economic disruption and significant negative effects of a disorderly exit.

Another aspect I suspect will also be welcome is the proposed “single customs territory”. This will remain in place from the end of the transition period until “the future relationship becomes applicable”. This means the UK’s tariffs and rules of origin are aligned to the EU’s and operate in an “agreed level playing field”, covering labour rights, tax, competition and environment.

One concern is how frictionless trade in goods will actually be. Another concern is that the single customs territory applies to goods not services. The latter of course includes financial services and the foreign investment inflows that come with them.

Although the Draft Withdrawal is mostly silent on services, the Outline of the Political Declaration document is more explicit, as it states the goal of “ambitious, comprehensive and balanced arrangements on trade in services and investment”.

Under financial services, it stipulates that equivalence assessments shall start as soon as the UK departs. The stated goal is to have them concluded “before the end of June 2020” (after which a decision to extend the transition period cannot be taken).

For business, the good news the deal brings is that short-term uncertainty has been minimised. Given the still very real possibility of a no-deal Brexit, this is arguably the best feature of the agreements. Yet the ad hoc and short-term features of these interim agreements do not bode well for long-term investment planning. The bad news is old news: a large part of the UK economy (financial services) still doesn’t know what the future entails.

The informed consensus remains that Brexit will make the UK permanently poorer over the long run and the agreement does little to change it. What the deal does is to establish that the economic costs will be smaller than in the case of a no-deal and that they are spread over a much longer period of time.

Maria Garcia, Senior Lecturer, Politics, Languages & International Studies, University of Bath

The Withdrawal Agreement sets out mechanisms to enable the smooth continuation of trade during the transition period (until December 2020), through the creation of a “single customs territory” made up of the UK and the EU customs union. During this period UK commercial policy would have to be in line with EU commercial policy, and the UK cannot make any trade deals with countries outside the EU.

The exact shape of the future relationship beyond 2020 will be the outcome of negotiations that will only start once the Withdrawal Agreement is approved by both the UK and EU. It is not sketched out in detail in either document that makes up the deal on the table.

But the list of topics when it comes to economic partnership beyond the transition period is comprehensive and in line with what the EU includes in modern free trade agreements (digital trade, intellectual property, government procurement, goods and services are all mentioned). The outline for future relations represents the special nature of this future agreement as it emphasises zero tariffs, fees, charges or quantitative restriction on all goods, and an ambitious customs arrangement.

How the customs arrangement will work after the transition period will be subject to negotiations and the degree to which there is alignment between UK and EU regulations. This would cover arrangements such as the levels of pesticides used in food and the chemicals allowed in paints. It should evolve from the single customs territory established during the transition period. But there is no reason to believe that the UK cannot have an independent trade agreement policy when the transition period ends. This depends on what long-term relationship the UK negotiates with the EU.

The references to services in the draft agreement indicate a desire on both sides to maintain as open a services trading regime as possible, although it is unclear what the ultimate negotiated outcome will be after the transition period. Indeed, the wording is not dissimilar to that found in other trade agreements (national treatment, non-discrimination, arrangements on professional qualifications), but the actual degree of market access normally appears in lists and annexes with exclusions, which, of course, have yet to be negotiated.

An important aspect is the inclusion of a commitment to begin work on equivalence assessments for financial services immediately after Brexit day, so as to limit disruptions to the sector. Both texts represent a compromise geared at minimising business and economic disruptions while the parties hammer out the practicalities of a future long-term arrangement.

Katy Hayward, Reader in Sociology, Queen’s University Belfast; Adrienne Yong, Lecturer at The City Law School, City, University of London; Maria Garcia, Senior Lecturer in International Relations, University of Bath; Michael Gordon, Professor of Constitutional Law, University of Liverpool; Nauro Campos, Professor of Economics and Finance, Brunel University London, and Phil Syrpis, Professor of EU Law, University of Bristol

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.