Dr Devyani Prabhat, Lecturer in Law, School of Law

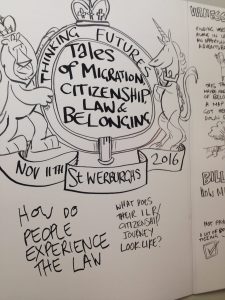

Last month I led an ESRC Funded Thinking Futures Event on Migration and Belonging at the St Werburgh’s Community Centre, Bristol. The event was attended by twenty-six people who had experience of applying for British citizenship or had personal stories to share about migration. Storytelling gives a direct voice to research participants and this was the theme of the event. Artist Sam Church who is a graphic artist simultaneously sketched the stories which were being shared.

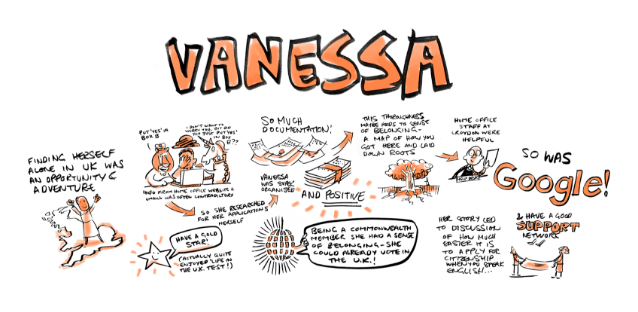

I kicked off the event with the story of Vanessa, an economic migrant from Botswana who had found the citizenship process a positive and empowering one. She had even found a typo in the Life in the UK test and the Home Office had thanked her for informing them about the printing mistake. As a commonwealth-national from a country where English is spoken, Vanessa felt she truly belonged in London. Her parents supplemented her income with additional financial resources such as help in buying a property. Vanessa was very organised about the paperwork she needed for her application. She treated it as an adventure; a personal quest to make sure she had more documentation than she needed for each element of her application. If she travelled abroad for work, she had human resources personnel from her office explain the absence from the country in a letter, and so on. Vanessa’s story prompted other stories from the participants, both positive as well as negative about citizenship applications. The expense of applications was a hurdle for most people. Rising costs are prohibitive for many.

Drawing by Sam Church

Stories bubbled up to the surface at the event. There was much laughter and shared emotion as people spoke of family migratory paths. A notable one involved an ex-colonial grandfather who had insisted that once he reached a century in age the Queen be informed of his death, and that he should not be buried until she was notified. He eventually passed away at the grand age of 105. He was located in Western Africa but perhaps felt more British than his grand-daughter who has grown up in Bristol and identifies with the city.

The event also featured some very talented actors who gave life to some of the other stories from my research participants. Interspersed amongst the tales of the other participants, the actors were the mainstay of the event. Interestingly, by the end of the event, completely out of script, they also shared their own migration stories. A strong sense of comfort with being British as well as having some other identity pervaded most of the stories as did a deep sense of regret against rising xenophobia and intolerance of immigrants in the UK in the current political climate.

Drawing by Sam Church

The stories shared further illustrated three key findings from my research. First, most people find the citizenship application process difficult and bureaucratic. Paperwork is the biggest challenge. Applicants’ perceptions of the legal process should be taken into account to simplify the application process. Second, most applicants who naturalise and have a certain level of educational attainment, appear to do their research and fill in their own paperwork without accessing legal advice. This is because they consider legal advice expensive and often not of an appropriate quality. These experiences raise concerns about the inaccessibility of affordable legal advice for those applicants who may not be as well resourced. It underlines some of the concerns we have raised for applicants who are in positions of vulnerability such as child applicants for citizenship who no longer have access to legal aid in nationality matters. Related to the above, it is unsurprising that a third consistent research finding is that successful applicants are those who are mostly resourceful, focused, and strategic about the application process. Determination sees people through. However, for citizenship applications to be fair and transparent, rather than a test of people’s mental strength, the information provided must be clearer and expectations consistent.

Above all, the event revealed how strong a need it is for human beings to belong somewhere. People have moved searching for better lives and security, but the everyday sense of well-being comes from a sense of home here. It was also surprising how much people had enjoyed their citizenship ceremonies; alternating between describing these as heart-warming or as ‘cheesy but fun’. While the local nature of the ceremonies was appreciated, there was also some bewilderment about their necessity when people have already identified strongly as British. There is a need here to reconsider whether citizenship ceremonies actually serve any deep purpose.

The positive spirit of community and belonging was clearly engendered by the sharing of stories; there is a lesson here for how productive consultations can be carried out in migrant communities through the story sharing methodology rather than emailed or printed forms being sent out as impersonal surveys to people. Consultations with migrant communities can be carried out in a positive and embedded manner. The stories shared at the events indicate that citizenship application processes must increase in simplicity, transparency, and fairness. In light of the Brexit spike in nationality applications, it is also important to increase accessibility to affordable legal advice.