Sarah Childs, Professor of Politics and Gender, School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies, University of Bristol

At home: In Westminster, Theresa May – the UK’s second woman Prime Minister – and in Holyrood, Nicola Sturgeon – Scotland’s first woman First Minister – opposed by the Tories’ Ruth Davidson, and Labour’s Kezia Dugdale.

Abroad: Angela Merkel, of course, and maybe soon President, Hilary Clinton.

The media seemingly don’t quite know what to do with ‘all’ these women in politics. Gender and politics scholars are finding themselves in great demand. There are, predictably, numerous articles in the newspapers about what the women are wearing, and how they do their hair.

PM visit to Germany July 2016 (l-r) Prime Minister Theresa May, Chancellor Angela Merkel. Tom Evans/Crown Copyright (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

They ask “Is May the new Thatcher?” as if there was only one ‘womanly’ way of doing politics. And find it rather surprising that the women hold different views, as if all women in politics must think the same way. And some even suggest that there’s been some kind of ‘women’s take over’ of politics – bar the Labour Party they quickly add.

Together the dominant story is that politics is now a place for women. Such a strong conclusion would be a misrepresentation. Women are not equal in terms of political participation and representation. Women’s leadership claims are not uncontested, as the motherhood debate clumsily illustrated; and women’s issues and perspectives frequently remain marginal to the political agenda. Women politicians – just like other women in public life – are often on the receiving end of misogynistic and violent social media.

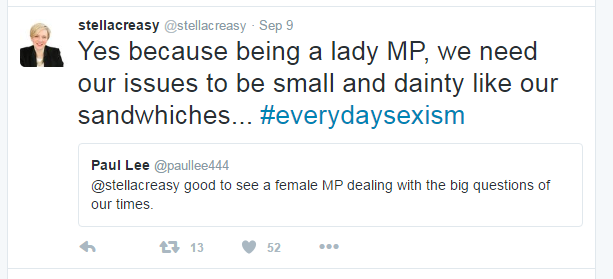

Screenshot from Stella Creasy MP for Walthamstow’s Twitter feed in 2016. In 2014, Peter Nunn was jailed for 18 weeks for sending rape and death threats to Ms Creasy via social media.

Equal representation?

Let’s start with numbers. At Westminster, as women MPs frequently remind folks, there are still more men sitting on the green benches in this Parliament than the number of women who have ever been elected to the House.

The Conservative Party may have its second woman leader in the Commons, but its parliamentary party remains 80 percent male; at 20 percent female its representation is only half that of women in the Labour Party; as a result of All Women Shortlists over 40 percent of Labour MPs are female. The Westminster Liberal Democrats have been all male since 2015.

So, there is nothing secure about women’s political presence. It requires a demand from parties and a supply of women.

![By WomanStats Project (http://www.womanstats.org) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://policybristol.blogs.bris.ac.uk/files/2016/09/Map3.8Government_Participation_by_Women_compressed.jpg)

A map of the world by governmental participation by women, 2010. By WomanStats Project [CC BY-SA 3.0 ], via Wikimedia Commons

Women in Power

What of women and leadership? Does a second woman Prime Minister for the Conservative Party ‘prove’ that the right are more conducive to women’s leadership, or that Scotland is more at ease with women in its ‘new’ devolutionary politics?

The theory of the ‘glass cliff’ apparently complicates assessment of May’s succession to Prime Minister. The glass cliff refers to the observation that, in business and in politics, women are allowed to be leaders only in times of crisis.

I would be wary of this explanation in UK politics at this time. First, and with only two cases at Westminster, it belittles May’s credentials. An evidently skilled Home Secretary should not be reduced to the representation of the ‘nanny’ clearing up the spilt milk. Secondly, it shifts the focus away from the inadequacies of the male leadership contenders. Academic attention should surely investigate why it was that all the leading men ‘fell’? Or more precisely, what is it about ‘masculinised’ politics that gave rise to them all exiting the stage in such an undignified fashion?

![By Steve Punter (http://www.flickr.com/photos/spunter/3079384811/) [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://policybristol.blogs.bris.ac.uk/files/2016/09/MichaelGove.jpg)

Former Cabinet Minister and Vote Leave campaigner, Michael Gove MP. By Steve Punter (CC BY-SA 2.0), via Wikimedia Commons

There may be something in the claim that rightist parties are apparently able to see the merit of particular individuals whereas the left, with its masculinised socialist traditions, has a certain unease with an equality that seems to privilege gender over class.

In the former case this is often tied to the claim that women leaders deny that gender is relevant to their leadership – but this isn’t true of May. Not only has she been active on women’s representation in politics for more than a decade, her liberal feminism arguably influenced her attention given to violence against women and girls in recent years.

Turning to Labour, it has considered but so far failed to institute a party commitment for gender balanced leadership (Leader and Deputy being male and female). A good number of Labour women MPs are clear – just check Twitter – that they are on the receipt of particularly gendered criticism at this time and take issue with any nostalgia for masculinised ‘Blue Labour’. New Labour’s feminism (notwithstanding some feminists’ criticism) unquestionably transformed the UK’s political agenda and is one of its significant legacies.

Harriet Harman QC MP, who led on and introduced the Equality Act 2010.

Credit – University of Salford Press Office

The feminisation of a political party is not signalled by a woman leader but is, rather, multi-dimensional. A political party that is feminised is one where women participate equally throughout the party – at the membership, activist, elected and leadership levels – and it is one where women’s concerns and perspectives are integral to its decision-making processes and outcomes. And then of course there is the feminist party: one that not only has women and women’s concerns running throughout its party structure but also one which places gender equality as central to its political programme.

Members of the Women’s Equality Party at Trafalgar Square during the Pride in London 2016 parade. By Katy Blackwood – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

What next?

A second woman Prime Minister proves once again that a woman can do the job. Symbolically this is a good thing. But I look forward to a time when it is no longer necessary to have this association between women and political leadership questioned. Nor is it the time for complacency in terms of the overall number of women in politics.

The next election– unless it is an early one – will see the number of MPs reduced to 600. There is a real risk that if the parties do not sign up to ‘no woman left behind’, that the numbers of women MPs will decline.

The recently published Good Parliament Report recommends that at the very minimum they should maintain their current percentages of women in the Commons. Finally, gender equality. On the steps of No. 10 Theresa May made this one of the defining features of her premiership.

Outside of the House, the Fawcett Society’s ‘Face Her Future’ and the WEP ‘100DaysofMay’ will hold her to this commitment.

Within Parliament, the Women and Equalities Committee, chaired by the Conservative Maria Miller MP, acting alongside Labour, SNP and Liberal Democrat MPs will formally scrutinise her government’s legislative programme.

There is no parity in British politics in 2016.