Mr Jamie Melrose, School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies

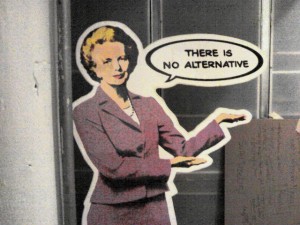

Lady Thatcher is no longer with us: the ideological project that bears her name, Thatcherism, is still alive, despite premature obituaries. Re-reading The Politics of Thatcherism[1] (PoT), an edited collection of essays as responsible as anything for Thatcherism’s definition, is rather relevant. If Thatcherism is still with us, it would make sense for the conclusions of PoT to be so too.

In some of the condemnatory criticism of Margaret Thatcher’s transformation of British political culture, there is a surprising political subtext: a grudging respect for how successful Thatcherism has been. Just as the Prime Minister admired his partisan rival, Tony Blair, critics such as Slavoj Žižek come to bury and praise Thatcher. Left-wing critics of Thatcherism look on in awe at that most difficult of tasks: hegemony in a pluralist demos.

This type of criticism has a history. In the early eighties, a group of critics associated with the journal Marxism Today savaged the Thatcherites’ colonisation of British public life, while backhandedly praising their brilliant recognition of the moment that was the crisis-ridden 1970s. Thatcher and her supporters recognised the intellectual bankruptcy of the traditional Labour and Conservative leadership in response to 70s stagnancy, and knew what to do. Marxist Today critics, foremost the cultural theorist Stuart Hall, drew on the Marxist theorist Antonio Gramsci, to explain how this was done. Importantly, the Marxism Today crowd gave Thatcherism an identity. This wasn’t familiar knee-jerk Tory populism; Thatcherism was something fresh and exciting ─ new times.

What does this Marxist Today critique in PoT tell us today concerning Thatcherism? From the perspective of analysing how heterogeneous political movements are successful or not, it has some telling Gramscian lessons. This makes it sound as if PoT is a collection of catechisms. It is, though, hard to miss certain statements which speak to a certain political activist, someone who is disenchanted with two forms of political understanding; namely, that politics is predetermined on the basis of class or pay packet, and that politics is a simple matter of acquiring executive authority and making something happen.

In PoT, one is reminded politics is about the moment: ‘[t]here is no guarantee that, because these opportunities exist, they will be seized or successful’ (Hall & Jacques, PoT: 15). As well as recognising that politics is engagement, one is also reminded that politics is a question of colonisation. A variety of institutions (such as universities, the popular press and companies) need to be attuned to ‘your’ view of the world. From reading PoT, politics is to be seen pragmatically. Despite idealist talk of a new order, Thatcherite activists were superb at taking contradictory beliefs and constructing ‘an alternate logic’ (Hall, PoT: 39). For example, authoritarian respect for law and order and hostility to an intrusive state (a sentiment also interestingly held on the anti-Stalinist left) were merged. Thatcherism wasn’t flawed because it combined liberal, individualist economics, ‘very alien’ (Gamble, PoT: 118) to one nation paternalist Conservatives, with militarised state intervention; it was cunning.

Moreover, Thatcherism wasn’t merely an efflux of the economy; it wanted to take industrial relations and remould them in favour of the capital-owning class (Rowthorn, PoT: 72). Thus, the Conservative Party under Thatcher became a crusading political entity in its own right (Gamble, PoT: 112-113). The left was not defeated because relations of production meant that the industrial worker was a thing of the past. It lost because it was unimaginative. It did not ‘have a purchase on practice’, the ability to give its ideas a certain ‘materiality’ (Hall, PoT: 39) in terms of articulating a coherent left-wing vision.

For Hall, ideas need to be micro-endemic to work; that is, as much at work in our workplaces and sports clubs as their board rooms and their cabinet meetings. To this end, PoT is a Gramscian letter to the left. Take our public institutions, full of leftist-liberal sentiments, yet precisely where governing Thatcherite rules of thumb on public institutional policy are embedded. Thatcherism has been domesticated; counter-hegemonic figurative politics are sidelined as exotic. PoT stands as testament that the right got and gets politics far better than the left.

[1] Stuart Hall and Martin Jacques (eds), The Politics of Thatcherism (London, Lawrence and Wishart: 1983).