Phil Syrpis, University of Bristol

After a bitter battle in which ministers were found to be in contempt of parliament, the UK’s attorney general, Geoffrey Cox, has published his legal advice to the government on Brexit.

At first reading at least, the advice seems to be sound. It accurately captures the legal situation surrounding the Irish backstop – which is that a “single customs territory”, with its rights and obligations for Northern Ireland and Great Britain, will exist from the end of the Brexit transition period “unless and until” it is superseded by a subsequent agreement between the EU and the UK which guarantees that there will be no hard border on the island of Ireland.

But it is sure to alarm many Brexiters, who have long insisted that the UK should have a unilateral right to end the backstop.

The government’s attitude towards both parliament and the public throughout this episode raises serious constitutional questions. And it prompts understandable alarm about the pledge for parliament to “take back control” of decision-making after Brexit.

No unilateral backstop exit

The legal advice is of limited scope and focuses solely on the legal effect of the Irish protocol set out in the Brexit withdrawal agreement. Although the advice was prepared on November 13, and therefore predates the withdrawal agreement between the EU and UK, it appears to be applicable to the final text.

Under the withdrawal agreement, the Irish protocol will only come into effect once the transition period has come to an end. This would be after December 2020, or, if an extension to the transition is agreed by the joint committee set up to oversee the withdrawal process, December 2021 or December 2022. Paragraph 16 of the legal advice is stark:

The ordinary meaning of the provisions … allows no obvious room for the termination of the protocol, save by the conclusion of an agreement fulfilling the same objectives … in international law the protocol would endure indefinitely until a superseding agreement took its place.

Cox then raises some points of EU law. He draws attention to the fact that there is a separation in EU law between the EU’s competence to conclude a withdrawal agreement with the UK under Article 50, and its competence to conclude a future relationship treaty with the UK. A future treaty is only possible under a different legal basis, once the UK has left the EU.

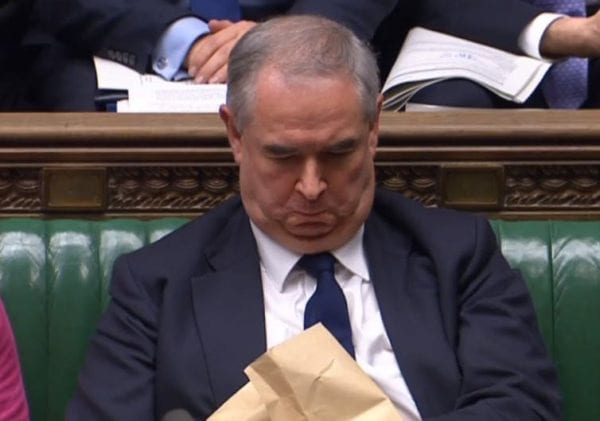

The attorney general, Geoffrey Cox: not amused. PA Wire/PA Images

While the attorney general concedes that the EU has the competence, under Article 50, to secure an orderly withdrawal, and to build a temporary bridge to the future, he argues correctly that Article 50 cannot be used to create enduring and wide-ranging future arrangements between the EU and the UK. He points out that uncertainty about the protocol’s consistency with EU law “will increase the longer it subsists”. These points are, once again, sound. Yet, in reality, it is unlikely that the Court of Justice of the European Union would rule that the withdrawal agreement is unlawful.

In his advice on the review mechanism for the backstop, the attorney general suggests that the UK failed “to negotiate a unilateral termination mechanism exercisable on notice”, for example, if it became clear that negotiations on the future relationship had irretrievably broken down. In Cox’s view, the protocol therefore: “Does not provide for a mechanism that is likely to enable the UK lawfully to exit the UK wide customs union without a subsequent agreement.” In the absence of a right to termination, he adds: “There is a legal risk that the United Kingdom might become subject to protracted and repeating rounds of negotiations.”

Overall, the attorney general’s advice captures the reality of the commitments the UK government has made in the course of its negotiations.

Reasons for MPs to be angry

Doubtless, the legal advice that the UK cannot withdraw from the backstop unilaterally is likely to alarm Brexiters, and has already angered the Democratic Unionist Party in Northern Ireland. But, most MPs will not have learned anything new.

The events of recent days have exposed the Government.

How can they possibly recommend such a bad deal to Parliament and the people of the United Kingdom? pic.twitter.com/Rxa9g4Uvi7

— Nigel Dodds (@NigelDoddsDUP) 5 December 2018

The deeper significance of this episode lies in what it reveals about the way in which this government operates. Despite some warm words, it has not levelled with the public about Brexit. It has not explained the nature of the fundamental choice which Brexit presents: either to seek close co-operation with the EU, and accept the legal and institutional implications of that; or to seek a more distant relationship, with greater independence, but with economic costs.

In 2017, the government went to extraordinary lengths to suppress the publication of its Brexit impact assessments, and it has now become the first government in history to be found be in contempt of parliament for its refusal to disclose Cox’s final legal advice.

Parliament and the devolved assemblies have particularly strong reasons to feel marginalised. The government took the activist Gina Miller’s case to the Supreme Court to seek to deprive MPs of a role in relation to the triggering of Article 50. It included unprecedentedly broad Henry VIII powers in the EU Withdrawal Act, constraining parliament’s ability to scrutinise ministers’ choices. It rode roughshod over the Sewel Convention, which requires the consent of the devolved legislatures, and has breached parliamentary conventions in relation to the pairing of MPs who cannot make it to the house in order to win key votes at Westminster.

The events of December 4, not just the contempt of parliament motion, but also the success of MP Dominic Grieve’s amendment that means parliament will have a say in what happens should Theresa May lose the vote on the withdrawal agreement on December 11, show that parliament is beginning to reassert itself. The attorney general’s advice serves to confirm the nature of the UK’s uncomfortable position under the withdrawal agreement. It is now for MPs to decide whether to back the deal, and, in the event that they don’t, to propose an alternative route forward and thereby avoid no deal in March 2019.![]()

Phil Syrpis, Professor of EU Law, University of Bristol

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.