Tusk and Juncker: nearly there. Image: Oliver Hoslet / EPA

Nieves Perez-Solorzano, University of Bristol

Before the Brexit negotiations had officially started, back in June 2017, the EU’s chief Brexit negotiator Michel Barnier told journalists what he needed on the other side of the table:

A head of the British delegation that is stable, accountable and that has a mandate.

Less than a year before Brexit day, scheduled for March 29, 2019, Barnier may feel he is still waiting for those conditions to be met, especially as the EU now finds itself with a new head of the British delegation, Dominic Raab. Raab’s negotiating position for the next round of talks, starting on July 16, results from Theresa May’s attempt to hold her cabinet and the Conservative Party together at a meeting at Chequers. In doing so, the prime minister provoked yet another domestic Brexit crisis with a spate of resignations, including those of the Brexit secretary, David Davis – who Raab has replaced – and foreign secretary, Boris Johnson.

In the face of such uncertainty, the reaction of the 27 remaining EU member states (EU27) to the UK’s new vision for a future UK-EU relationship has been cautious but unenthusiastic. European leaders from Barnier to German chancellor Angela Merkel, and from Irish premier Leo Varadkar to Sebastian Kurz, the Austrian chancellor whose country holds the EU Council presidency, have spoken with one voice. They have all welcomed the British government’s attempt to define a negotiating position on the framework for the future UK-EU relationship, but have asked for further detail.

Read more:

The Brexit plan that could bring down the British government – explained#

As one EU diplomat recently put it: “We will try to receive it as well as possible but from what we understand it is still a carve-out of the single market.” The diplomat added that May’s proposed single market for goods is, “A lot of fudge with a cherry on top.”

The final stretch

European leaders are also concerned that time is running out for a deal to be finalised – even as Barnier indicated: “After 12 months of negotiations we have agreed on 80% of the negotiations.” This may be read as a reminder to the UK government not to divert too much from what has been achieved at the negotiating table so far – and an expectation of more clarity, soon.

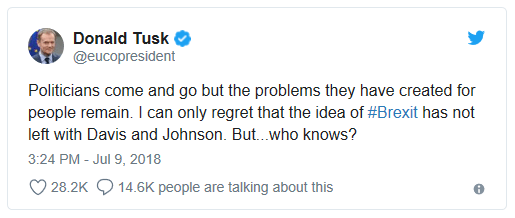

Some have seen a recent tweet from Donald Tusk, president of the European Council, in the wake of the UK cabinet resignations, as an opportunity to reverse Brexit altogether.

The EU’s reaction to the detail of the British position will be shaped by the challenge of having to negotiate with an increasingly unstable British government while trying to avoid a “no deal” scenario. Even though European Commission president, Jean-Claude Juncker, has confirmed that the EU has started preparations for this eventuality, the EU is committed to an orderly British withdrawal that avoids uncertainty and protects citizens and businesses.

The EU’s reaction to the detail of the British position will be shaped by the challenge of having to negotiate with an increasingly unstable British government while trying to avoid a “no deal” scenario. Even though European Commission president, Jean-Claude Juncker, has confirmed that the EU has started preparations for this eventuality, the EU is committed to an orderly British withdrawal that avoids uncertainty and protects citizens and businesses.

On a frenetic day at Westminster, May found time to meet Austrian chancellor, Sebastian Kurz, at Downing Street. Rick Findler/EPA

And while the EU27 will not do this at any price, it’s in this commitment to a final Withdrawal Agreement that the member states may find the political will to work constructively with the UK’s current vision for a future relationship even if there are fears that May’s government could fall at any point.

Extend the Article 50 deadline

So how might the EU do this? First, it can agree to extend the Brexit negotiation process. This might not have been a preferred outcome at the start of the negotiations, but if extending the negotiation period ensures that there is an agreed solution that avoids a hard border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland and thus UK agreement on the Withdrawal Agreement, the EU27 are perfectly justified in drawing on this flexibility tool. The terms of Article 50, which govern the procedural requirements for a member state to be able to exercise its right to leave the EU, allow for the deadline to be extended beyond the initial two years.

Read more:

What is Article 50 – the law that governs exiting the EU – and how does it work?

The UK and all EU member states must agree to the extension. Given its internal crisis, the UK government might welcome a softening of the ticking Brexit clock pressure. Even though Brexit day is enshrined in the EU Withdrawal Act, ministers can change it if necessary. May confirmed that this would only happen in “exceptional circumstances” and “for the shortest possible time”.

For their part, the EU27 need to unanimously agree to the extension. The experience of other highly politicised negotiations such as the accession of new countries, has shown that the member states are able to leave aside their egoistic national preferences to pursue the collective EU interest – namely avoiding a disorderly Brexit.

Softening red lines

Second, the EU may decide to soften some of its red lines for the purpose of finalising a Withdrawal Agreement. Barnier hinted at this in a speech on July 6, stating “I am ready to adapt our offer should the UK red lines change”, but making it clear that the integrity of the single market had to be protected.

If the forthcoming white paper can offer sufficient detail and some realistic substance for the EU negotiating team to work with, and if the UK and EU can find sufficient common ground on such detail, this might afford some leeway to get the negotiations over the hurdle of completing a Withdrawal Agreement. As Franklin Dehousse, a former judge at the EU General Court has put it:

There are no serious legal reasons to exclude a Brexit deal with single market on goods and partial free movement of people (but with the proper institutional guarantees). Obstacles are political, and if people want to create them, they should justify them as such.

The Brexit challenge is no longer an existential threat to the EU but rather to the Conservative government. However, the future of the EU depends on the success of the Brexit process and this requires a degree of ingenuity and political will that allows it to consider Brexit scenarios that protect the integrity of the bloc and its member states, without marginalising the UK.

Nieves Perez-Solorzano, Senior Lecturer in European Politics, University of Bristol

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.