Why should we care about mature students?

It has become almost routine to read stories giving ‘more bad news’ about part-time student numbers in universities.

Tom Sperlinger is Reader in English Literature and Community Engagement at the University of Bristol.

Lizzie Fleming is Widening Participation and Student Recruitment Officer, and a postgraduate student, at the University of Bristol

On 29 June, the Office for Fair Access (OFFA), which monitors access to universities in the UK, published its outcomes for 2015-16. The report highlights a ‘crisis’ in part-time numbers, which have fallen for a seventh consecutive year, a decline of 61% since 2010-11. Since more than 90% of part-time students are over 21, this has also led to a significant decline in the number of mature students in the sector.

This also means that, overall, the number of students entering universities has fallen significantly since 2012.

If you read some of the good news in OFFA’s report, you might wonder why this decline in part-time and mature numbers matters. The caricature of a mature student is a wealthier person taking a degree for leisure later in life. Meanwhile, UCAS data for the 2016 cycle shows that 18 year-olds from neighbourhoods that have traditionally had low participation are entering higher education at a higher rate than ever before: 29% higher than in 2012-13.

But the decline in mature students matters deeply for a whole variety of reasons:

- If we really want to address widening participation, then we need to work with mature students, as they are more likely to be from disadvantaged groups.

- Adults and the diversity and life experience they bring is valuable to the learning environment.

- The number of under 18 year-olds is decreasing, so the sector needs to adjust.

- To influence young students from disadvantaged backgrounds, parents and other adults are key – and one person can end up changing participation in a whole community.

What do we know about mature students?

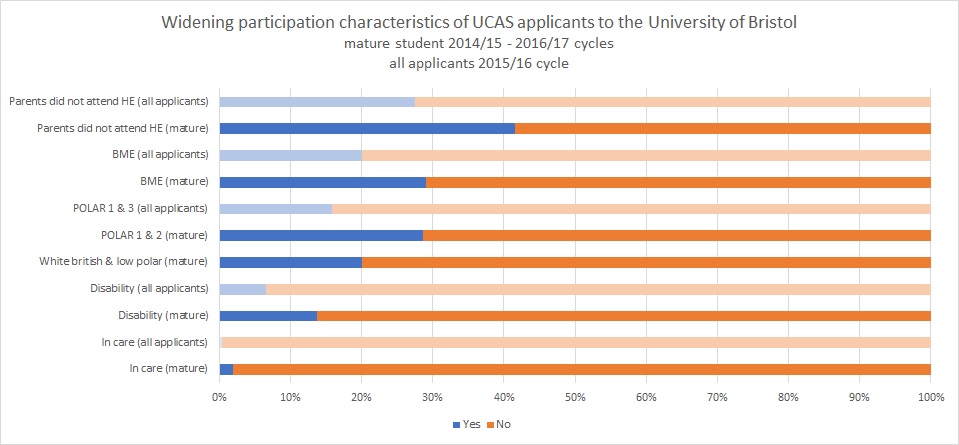

Data we have collected on mature applicants from three UCAS cycles to the University of Bristol (see Figure 1) shows that mature applicants are much more likely than standard-age applicants to be:

- the first in their family to attend university;

- from an ethnic minority;

- from a lower socio-economic group;

- to have a disability;

- or to have grown up in care.

On some of our courses that are designed to cater for mature students, such as the Foundation Year in Arts and Humanities, we’ve also found that students who have taken time out of education, whether they are 18 or 25 or 75, are much more likely to have experienced multiple forms of disadvantage.

In other words, the 61% drop in part-time students since 2010 represents a catastrophic loss of opportunities for some of those already most excluded from higher education. New work with mature students is vital if universities, and the government, are serious about involving those from lower socio-economic groups, ethnic minorities and communities with little or no contact with higher education.

Figure 1. Widening participation characteristics of UCAS applicants to the University of Bristol, mature student 2014/15 – 2016/17, all applicants 2015/16 cycle

What can be done?

Today the Open University is launching a new report on outreach with disadvantaged mature students, for which the Foundation Year at Bristol has been one case study, alongside courses at the OU, Birkbeck and Leeds. The report shows that imaginative and flexible outreach can help adults with few conventional qualifications go on to success in higher education.

So how can this work be replicated on a larger scale?

The report suggests that OFFA should require institutions to spend a dedicated amount of their access agreement money each year on outreach with disadvantaged adult learners.

It also provides a new tool for institutions to assess whether they currently have a whole-institution approach to supporting adult learners. You can try out the tool and see how your institution fares. Such an approach is vital if such work is to be integral and not just an optional extra, and it could form part of a larger strategy to create a whole-institution approach to diversity.

We suggest going further. Why not require all institutions to take 20% of their admissions in future via a route in which no prior qualifications are required? The Open University has led the way in this area. Our experience with the Foundation Year has also taught us that such a system can be more rigorous than the standard entry via A-Level grades. Students on that course complete an application form, written work, and attend an interview as part of the admissions process. Over 90% of students have completed the programme successfully, even though nearly the same percentage did not have A-Levels when they started.

Too often mature students are thought of as an optional extra in a mass higher education system built for younger people. But, at a time of growing debate about why social mobility has stalled, it is time to celebrate anew the radical potential of adult learning. An upsurge in the number of mature students would be good news for the whole sector.