Dr Angeliki Papadaki, Lecturer in Nutrition, School for Policy Studies, University of Bristol

I come from Crete. I grew up in a house where everything revolved around the kitchen. Most of my childhood memories involve my mother preparing meals from scratch, using olive oil. Meals were accompanied with vegetables and we had a legume soup (like lentils, beans, chickpeas) twice a week. All of them were a pleasure to eat; they just needed olive oil and a slice of bread to scoop up the juices to receive a cook’s highest reward: empty plates.

I’ve lived in the UK for 10 years and I still can’t enjoy vegetables or salad unless I prepare them myself. They are boiled and boring, with uninspiring dressings, and no tomato sauce or sautéing with olive oil and onions to give them some flavour. It’s no wonder that 70% of adults in the UK do not eat enough fruits and vegetables and that on average they consume 14g of legumes a day (half the amount consumed in the traditional diet of Crete).

Credit – pixabay.com

The argument that olive oil, as one of the most important Mediterranean diet foods, helps the consumption of higher amounts of vegetables and legumes is not new. Yet UK dietary guidance has a long tradition of recommending a low-fat diet. Up to recently, the Eatwell Plate recommended to “eat just a small amount of foods high in fat” and made only one reference to olive oil: “When you’re cooking, use just a small bit of unsaturated oil such as sunflower, rapeseed or olive, rather than butter, lard or ghee”.

Granted, the revised Eatwell Guide differentiates unsaturated oils from other high-fat foods, but still emphasises that these foods “should be limited in the diet”, without defining this limit. Again, olive oil comes third in line, after vegetable and rapeseed oil. To contrast this, the Mediterranean diet recommendations suggest that olive oil should be the main source of fat in the diet and used in every main meal. A recent randomised controlled study showed that for each 10 g/day increase in extra-virgin olive oil consumption, cardiovascular disease incidence and mortality decrease by 10% and 7%.

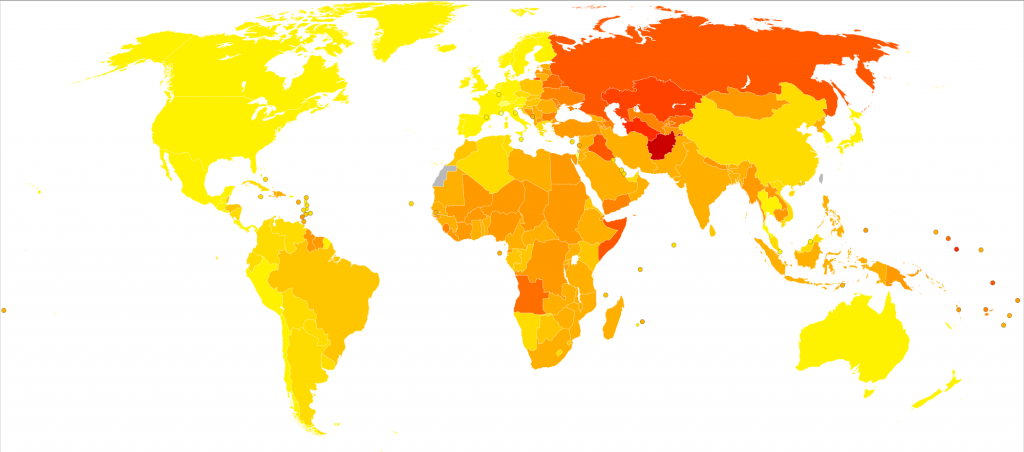

Disability-adjusted life year for cardiovascular diseases per 100,000 inhabitants in 2004. Credit – Wikimedia Commons

The concern about moving from a low-fat diet recommendation to a higher-fat one (even with the ‘right’ fats) might come from fear of promoting obesity. Yet, despite the advice to limit fats, more than half adults in the UK are overweight or obese. At the same time, diabetes is on the increase and heart disease is one of the most common causes of death. In contrast, and despite its higher fat content, the Mediterranean diet does not cause weight gain, and even if some heart disease risk factors are higher in Mediterranean countries, actual diagnosis of the disease is lower than in the UK. High-fat diets were recently shown to improve risk factors for heart disease among people with diabetes, compared to low-fat diets. The Spanish landmark PREDIMED study also recently showed that following a Mediterranean diet, with high amounts of olive oil (≥4 tablespoons recommended every day), reduces risk of cardiovascular events by 30%, compared to a low-fat diet usually recommended for the prevention of cardiovascular disease.

A typical Greek salad with feta cheese. Credit – pixabay.com

The EU recently invited its Member States to “promote healthy eating, emphasising health promoting diets, such as the Mediterranean diet”. The US Dietary Guidelines have also recently recommended the Mediterranean diet as an example of a healthy eating pattern. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, after reviewing the evidence for its draft public health guideline on maintaining a healthy weight, recommended to “follow the principles of a Mediterranean diet, which is a diet predominantly based on vegetables, fruits, beans and pulses, wholegrains, fish and using olive oil instead of other fats”. After review by the Public Health Advisory Committee however, this recommendation was not included in the final guidance, exposing a resistance of UK experts to the Mediterranean diet recommendations.

A meal in Greece. Credit – Pixabay.com

Yet we know that the Mediterranean diet is tastier and easier to comply with compared to a low-fat diet. We know that, with appropriate nutrition education, it can be transferable to Western populations. Perhaps we need to show its effect on health through randomised controlled trials in the UK before we see UK dietary guidance embrace its recommendations, similar to what our US counterparts did.