Dr Martin Hurcombe, Reader in French Studies, University of Bristol

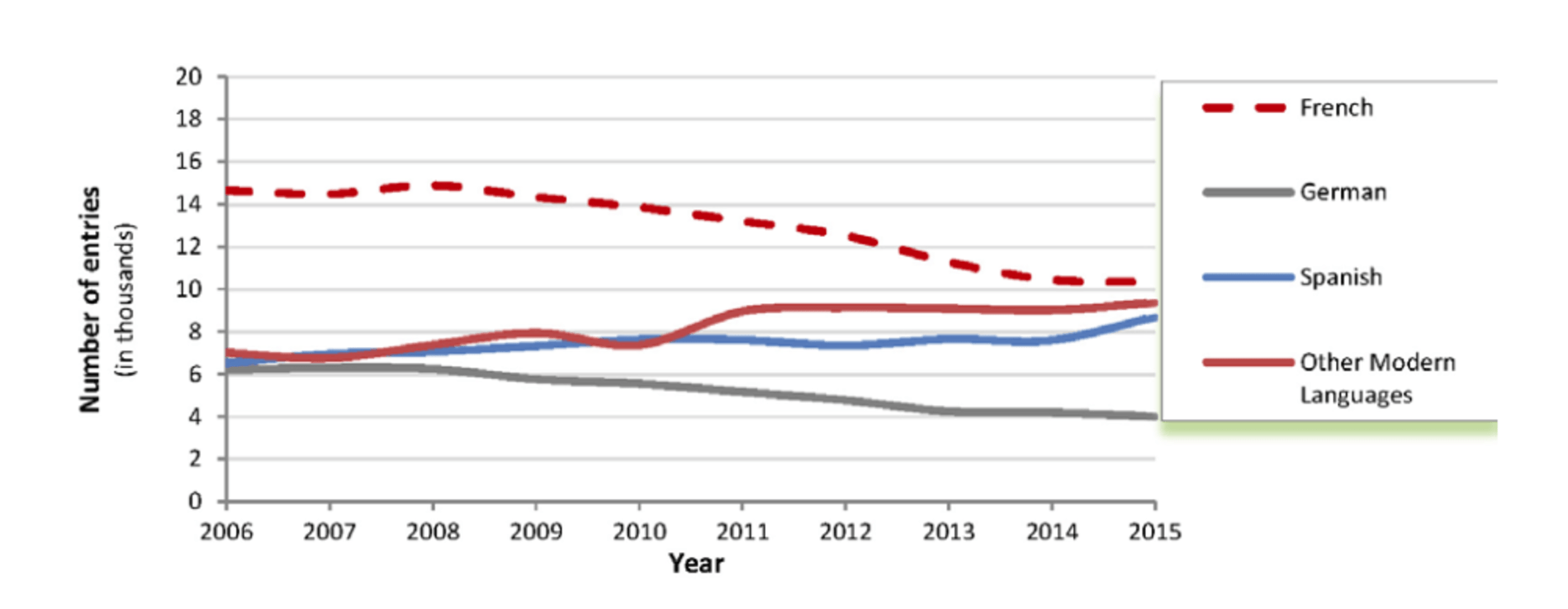

The decline in the number of students of modern languages from GCSE to degree level is an annual lament. Only 10,328 pupils in the UK took French at A Level in 2015 and although Spanish enjoyed a rise in entries at A Level of 14%, German continued its steady decline.

As Vicky Gough, schools adviser at the British Council, noted last year, the study of French and German at A Level has declined by more than 50% since 1999.

Similar patterns can be observed at GCSE where entries for French, for example, declined by 40% between 2005 and 2015. The rise in interest in Arabic and Portuguese has not offset the overall trend towards the marginalisation of language learning in Britain’s secondary schools, and most notably those in the state sector.

A Level language entries, 2006-2015. JCQ

It’s hard for language learners and teachers to remain optimistic in this climate, and harder still with widespread Euroscepticism and the possibility of the UK voting to leave the European Union in a referendum on June 23.

Policy ping pong

For teachers like me, entering the profession in the late 1980s and early 1990s amid a brief bout of Europhilia, language education was still a priority. When the National Curriculum was introduced in 1988 all secondary schools had to make provision for students of all abilities to learn at least one modern foreign language.

Paradoxically, this enthusiasm for language learning in the years preceding the 1992 Maastricht Treaty and the foundation of the European Union emanated from a series of Conservative governments that were tearing themselves apart over the question of European integration.

Nevertheless, it was made compulsory for children to learn one modern foreign language. This was because of a belief by those in government and business that not only was it desirable to speak more than one language, but that a meaningful relationship with European partners was best served by the cultural familiarity that language learning fosters.

Ironically, it was perhaps Britain’s most pro-European government, under Tony Blair, which removed the requirement for all children to take a language at GCSE in 2004. Only now are we seeing this decision reversed with the current government’s inclusion of a language at GCSE as one of the performance measures schools are judged on.

Since the late 1990s there has also been a decline in school exchanges in state schools – a tradition in many schools that had become firmly established with the UK’s membership of the common market. According to the British Council only 39% of state schools currently offer an exchange where students stay with a host family in another country – compared to 77% of independent schools.

Identikit travel

The decline in the study of languages has also coincided with a decline in the chance for young people to have genuine cultural encounters with Europeans on the continent.

Week-long holidays to the Algarve or southern Spain often bring little in the way of cultural exchange. Experience of travel to Europe can sometimes be restricted and characterised by a sense of familiarity: airports that resemble each other, the ubiquitous Starbucks, the identikit sites of global tourism observed by Paul Fussell in the 1980s and dubbed non-places by French philosopher Marc Augé.

Yet travel and the encounter with other cultures and peoples can challenge our fundamental beliefs. It shakes us from our complacency and forces us to rethink who we are in the light of other customs and habits. We return home to ask new questions of our lives, but also of our surroundings. While this can be a destabilising experience, it is also a highly productive one with benefits for both our sense of self and the home to which we return, which is now viewed through fresh eyes.

Learning a new language has a similar effect on one’s sense of self: it enhances such cultural exchanges and enriches travel. The study of languages is not the study of linguistic abstractions – it’s the study of cultures.

The paradox of current government policy is that it talks about the importance of global trade and competitiveness while doing little to prepare the next generation of UK citizens for the future it envisages. If Britain votes to leave the EU, it will merely confirm a policy of cultural retrenchment initiated by the Labour governments of 1997-2010. If the country votes to remain, it must be accompanied by a commitment to the European project as a cultural and not merely an economic enterprise.

And we must also recognise that learning the languages of our EU partners is often the gateway to speaking to the world at large.

Martin Hurcombe, Reader in French Studies, School of Modern Languages, University of Bristol and curator of the Europe and Me blog.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.