Terrell Carver, University of Bristol

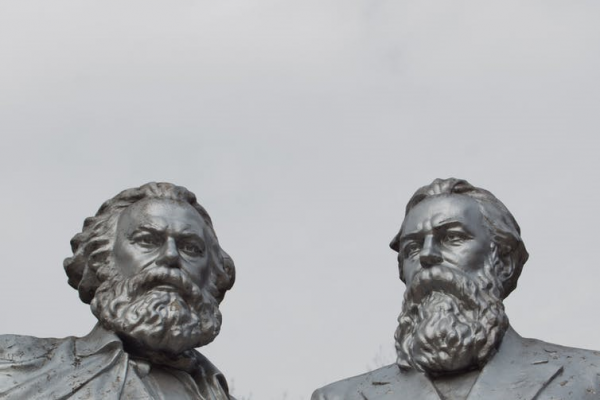

Backgrounding Marx is hard to do, especially when 2018 is the 200th anniversary of his birth and a huge number of global events are focusing on the great man. This is his usual “leader of the orchestra” position, with his life-long friend, constant benefactor and sometime co-author Engels in his usual role as second fiddle. But another 200th anniversary is fast approaching: that of Engels’s birth in 1820. Best to be forewarned and forearmed.Engels has recently become something of a character and a condundrum, hard on the coat-tails of Francis Wheen’s prize-winning “humanising” biography of Marx. In particular, Tristam Hunt’s popular recent biography, The Frock-coated Communist, presents the colourful life of a factory-owner’s son turned communist agitator, yet at the same time a respectable Manchester businessman – who rode to hounds with the Cheshire Hunt.

And Engels has recently been fictionalised in an unusual novel, Mrs Engels by Gavin Macrae. “Mrs Lizzie,” Engels’s partner-cum-housekeeper, recounts his later life and times in the first person. On the death of her sister Mary in 1863, she succeeded to a similar place in Engels’s affections and domestic affairs, and their similarly unmarried association – remaining so until he married her on her deathbed in 1878 – gives readers a working-class Irish view of the man in her life.

Having supported Marx and his family financially for many years, even occasionally fulfilling his contracts for paid journalism and hack-writing, Engels came into his own after Marx died in 1883. Engels survived him by 12 years and made a success of his posthumous partnership. He published new editions of the master’s works, introduced by himself, the lifelong comrade-in-arms. And he also authored independent works, starting in the 1870s, following on – so he said – in the master’s footsteps, but gaining a much wider readership.

Marxism as a political ideology postdates Engels, but most of the ideas in it were lifted directly from his version of Marx.

Engels before Marx

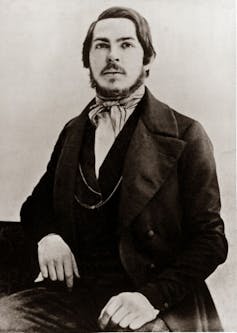

Wikimedia Commons

Engels the man has lately replaced Engels the Marxist, but there is more to the recent Engels revival than that. The very early Engels was quite the firebrand radical, excoriating the burghers of his twin-city hometown (Elberfeld and Barmen, now Wuppertal in Germany) for their visibly exploitative, and highly polluting, industrial spinning and weaving enterprises. At the age of 18, he wrote triumphantly to a school friend that his anonymous publication, in a local paper, had really riled the respectable classes.

The juvenile Engels was already the radical. He sympathised with the fashionable struggle for Greek independence from the Turks, and supported liberating German society and culture from the non-constitutional, semi-medieval monarchies and dukedoms that were reinvigorated after Napoleon’s defeat. He was also behind shockingly egalitarian reforms even to family and sexual relations. His career as a published literary critic took off after his education finished (at 16), and he proceeded under pseudonyms, disguising his neglect of his day job at the Manchester branch of the family firm, where his parents sent him to work aged 22.

Working at Ermen & Engels cotton-spinners in Salford, among the “satanic mills”, Engels encountered Chartism, the movement to broaden the suffrage to more males than a very select few. He swiftly became a correspondent for The New Moral World and The Northern Star, fluent in passionate English. By the late summer of 1844, when he met Marx for the second time (Marx had treated him dismissively on the first occasion) Engels had published nearly 50 items in two languages, many more than Marx.

Wikimedia Commons

Glory days in Manchester

Here is where we encounter Engels’s last work that was independent of his association with Marx, The Condition of the Working Class in England, a full-length, German-language study published in 1845, when Engels was 25. He was understandably pleased with his achievement at the time, and was happy to republish it in 1887, marking 40 years of class struggle. It has been in print since then in many translations, and is currently a classic with both Oxford University Press and Penguin Books.

Engels worked from contemporary sources, mostly parliamentary reports and inquiries that detailed the poverty and misery of factory work. But – rather in advance of his time – he ventured into the slummy depths of the back-to-backs and airless basements into which penniless wage slaves were crammed. His access to these scenes was facilitated by Mary, his first Burns-sister partner. As an eyewitness founder of urban geography, drawing detailed maps and diagrams to make his writing vivid and persuasive, he was at the cutting edge.

![]() And so Engels poses more questions today for us than we can instantly answer, given the billions of people living in slums across the world that Mike Davis and other urban geographers, radical architects and global campaigners have pictured for us and exhaustively analysed. The Occupy movement took over public spaces to highlight contemporary conditions and other aspects of global capitalism that match Engels’s descriptions exactly. This, then, is certainly a moment to bring Engels’s shade out of the shadows.

And so Engels poses more questions today for us than we can instantly answer, given the billions of people living in slums across the world that Mike Davis and other urban geographers, radical architects and global campaigners have pictured for us and exhaustively analysed. The Occupy movement took over public spaces to highlight contemporary conditions and other aspects of global capitalism that match Engels’s descriptions exactly. This, then, is certainly a moment to bring Engels’s shade out of the shadows.

Terrell Carver, Professor of Political Theory, University of Bristol

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.