The British Home Office has created a bureaucratic nightmare for EU citizens applying for permanent residency. Might there be a better way forward?

According to official figures there are over three million non-UK EU citizens living in the United Kingdom, many of which live in Bristol. Following the referendum of 23 June 2016 and the notification by the UK government to withdraw from the European Union many of those citizens are naturally feeling anxious about Brexit and the future of their rights in this country. What will happen to them once the UK leaves the EU is still unclear. In the Guidelines Following the UK’s Notification under Article 50 TEU adopted on 29 April 2017, the EU 27 recognise that “the United Kingdom’s decision to leave the Union creates significant uncertainties that have the potential to cause disruption”, notably for “[c]itizens who have built their lives on the basis of rights flowing from the British membership of the EU [and] face the prospect of losing those rights”.

According to official figures there are over three million non-UK EU citizens living in the United Kingdom, many of which live in Bristol. Following the referendum of 23 June 2016 and the notification by the UK government to withdraw from the European Union many of those citizens are naturally feeling anxious about Brexit and the future of their rights in this country. What will happen to them once the UK leaves the EU is still unclear. In the Guidelines Following the UK’s Notification under Article 50 TEU adopted on 29 April 2017, the EU 27 recognise that “the United Kingdom’s decision to leave the Union creates significant uncertainties that have the potential to cause disruption”, notably for “[c]itizens who have built their lives on the basis of rights flowing from the British membership of the EU [and] face the prospect of losing those rights”.

Clarifying the status of EU citizens could have been done unilaterally by the British government. It chose not to, however, arguing that the status of UK nationals in EU states also needed to be addressed and reciprocal rights offered. Although the issue was raised in parliament during the debate over the European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Bill legal uncertainty remains. The European Union has on several occasions stressed that finding a solution to this issue was paramount and needed to be tackled at an early stage of the Brexit negotiations. Indeed as stressed in paragraph eight of the EU 27’s guidelines, “[t]he right for every EU citizen, and of his or her family members, to live, to work or to study in any EU Member State is a fundamental aspect of the European Union”.

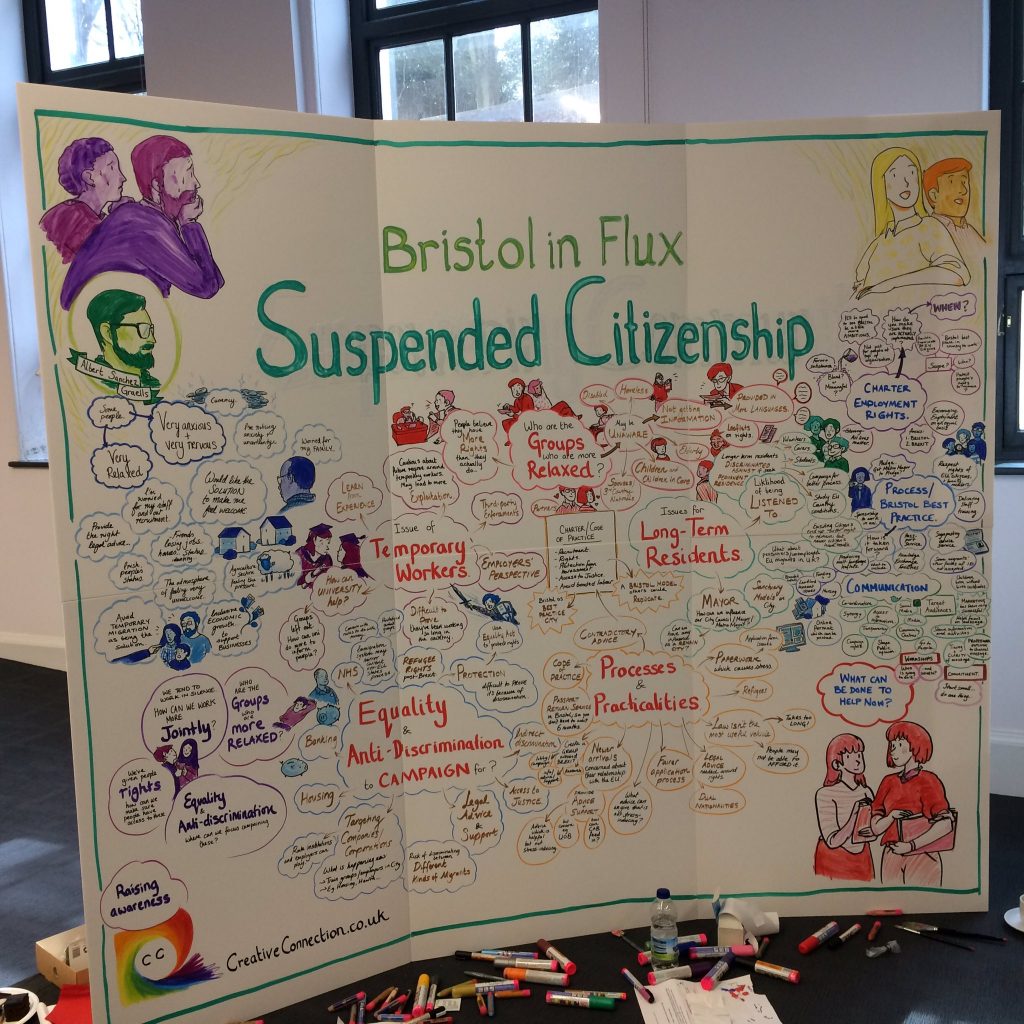

This was the main theme of the workshop ‘Bristol in Flux: Suspended Citizenship’ organised by the University of Bristol on 3 April 2017 to which we, as lecturers in EU Law at the University of the West of England and authors of the textbook European Union Law, were invited. One of the subtopics broached at the workshop was the fate of long-term EU residents who seem to be most affected by Brexit. The debate predominantly centred upon two themes of immediate practical relevance: first, the conditions for obtaining a UK status, and second, the processes and practicalities of transforming their EU status into a UK status.

Seeking solid ground

At the moment, European citizens automatically acquire permanent residency after five years of residence in another EU country under Article 16 of the EU Citizenship Directive. Currently under EU law there is no need for a document to confirm permanent status in the UK. However, to mitigate potential loss of residency rights in the wake of the referendum, some EU citizens applied for permanent residency in the UK.

To obtain such documentation one needs to satisfy a number of fully documented requirements. What initially seemed to be ‘straightforward’ paperwork turned into a shock for EU citizens who discovered they did not meet the basic requirements despite long-term residence in this country and were regarded as being potentially unlawful residents. Those most affected were economically inactive EU citizens without private health insurance, individuals who had recent breaks in their careers, EU citizens married to or in unmarried relationship with British nationals, pensioners, long-term disabled persons, individuals in care homes, etc.

A common problem appeared to be that they did not hold a comprehensive sickness insurance cover. In contrast, those in employment for the past five years did not appear to face such hurdles. There is no doubt that the current conditions for obtaining permanent residency tend to discriminate against students, individuals who have been volunteering, individuals who have been in and out of jobs, etc., all of whom seem to be seen by the current government as not effectively contributing to the national economy and thus not worthy of continued membership in British society.

A quick glance at the government website to apply for such documentation of permanent residency gives the wrong impression that the application and its process are simple and straightforward: one needs to fill in a form (online or on paper) and attach a couple of supporting documents. The reality could not be any more different as the form is 85 pages long – though probably only 50 are to be completed depending on one’s status – and there is a plethora of supporting documents to provide and enclose. It is telling that the guidance, which was updated on 27 April in light of the increase in applications, is 40 pages long.

A bureaucratic nightmare

Many EU citizens have faced unsurmountable hurdles trying to document their employment and/or residence in the UK. Who keeps electricity bills for five years? As a result a number of EU citizens’ applications have been rejected on the ground that they were not able to enclose the supporting documents.

One of the questions discussed at the workshop was the burden of proof. Could it be transferred to someone other than the EU applicant – e.g. the employer or government bodies – and could there be easier ways of providing supporting documentation? For instance, it was suggested that maybe HMRC records could be accessed directly by the Home Office in order to establish that economically active EU citizens fulfilled the requirements. Another proposal was that employers of EU citizens could, with the consent of the employee, directly provide employment records to the Home Office. This could be of particular use for large companies or educational institutions such as universities that employ large numbers of EU nationals. Locally, employers that could benefit from such measures would be, for example, Airbus, the University of Bristol and the University of the West of England.

The application procedure was also criticised as being too cumbersome and there were many calls to simplify it. It was suggested at the workshop that the permanent residency application procedure is much smoother in other EU countries, such as Germany, and that the UK could adopt similar forms and processes. The European Commission’s Directives for the negotiation of an agreement with the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland setting out the arrangements for its withdrawal from the European Union specifically provides that any document issued to EU citizens in relation to their residence rights arising from Articles 21, 45 and 49 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) and the Citizenship Directive “should have a declaratory nature and be issued under a simple and swift procedure either free of charge or for a charge not exceeding that imposed on nationals for the issuing of similar documents” (para 21(b)(i)). The implementation of such a proposal is no doubt welcome all the more as the British government appears to be swamped by applications it is unable to process. Indeed, it has recently asked EU citizens to refrain from applying for permanent residency and encouraged them to sign up for email updates instead.

The recent revelations in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung about the Juncker-May dinner are not going to reassure EU citizens, for it was reported that Theresa May suggested that the UK and the EU agree swiftly at the next European Council meeting in June that EU citizens be simply given the status of third country nationals. This proposal is, however, unlikely to meet the demands of the EU 27 who wish “to safeguard the status and rights derived from EU law at the date of withdrawal of EU and UK citizens, and their families” (para 8 of the European Council Guidelines). Furthermore, how this en masse change in status would be processed is even more unclear.

Clearly, the solution preferred by long-term EU residents to alleviate their fears is one that enables them to keep exercising their acquired rights through smooth and simple administrative procedures. An agreement between the EU and the UK along the lines suggested by the commission is likely to fulfil the wishes of EU citizens in the UK. Undoubtedly, for many EU citizens, an automatic transformation of EU citizenship rights is the way forward.

#BristolBrexit – A City Responds to Brexit

#BristolBrexit – A City Responds to Brexit is a free public event at @Bristol on the 23rd of May from 10.00-13.00. The event, organised by the University of Bristol in collaboration with the University of the West of England and the University of Bath brings together stakeholders, practitioners, activists, educators, business people, city officials, religious leaders, and charity representatives to collectively and collaboratively address the challenges of uncertainty brought about by Bristol. The event will feature a series of interactive formats to bring representatives from across the city together to develop new and innovative strategies for taking Bristol into the future.

All are invited: register here.

Christian Dadomo is senior lecturer in law at the University of the West of England.

This article was first published by openDemocracy under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International licence.