Denny Pencheva, PhD researcher in Politics; Teaching Assistant in Politics, SPAIS, University of Bristol

In light of the EU referendum result, a lot has been said and written on why Britain voted to leave. From my own point of view, as an Eastern European migrant and an aspiring academic, the Leave victory was not so much a surprise, but rather a long-feared reality. Just to be clear, it is not that a sensible case for an EU exit could not have been made, it is that it was not made.

When I came to Britain I knew I was not in continental Europe, but I knew I was in the EU. And this offered some consolation in terms of guaranteeing the so-called acquired rights, given the numerous legal opt-outs Britain has within the EU, including on issues of immigration.

In light of my research around issues of asylum and migration, EU border control policies and more (see base of blog for detail), I want to examine how British mainstream media played a role in framing the main debates ahead of the EU referendum campaign and ask, what are the policy and real-life implications for British and EU citizens?

Free movement = uncontrollable immigration

Putting aside the media’s failure to promote any sense of European belonging, my data analysis shows that media outlets have systematically and for at least a decade, merged the concepts of Europe with (uncontrollable) immigration. The principle of free movement has been gradually but steadily associated with mass, uncontrollable immigration.

Check-in and passport control at the Eurostar station in Brussels, Belgium. Credit – Opihuck/Wikimedia Commons

Across editions and publication types, the EU has been narrated as an undemocratic and oppressive structure which is undermining Britain’s sovereignty and its ability to control its own borders.

Tabloid editions have been particularly vocal in expressing concerns that immigration rules apply to Australians, but not to Romanians; that in order to keep net immigration down, less Indians were allowed in the country to study or set up businesses.

In 2013, Nigel Farage even suggested that Britain was not doing enough to protect Syrian refugees because it was overwhelmed by Bulgarians and Romanians.

EU migrants vs expats

For the media, it has been difficult to understand that legally speaking, these people are not migrants; they are EU citizens who lawfully exercise their acquired rights; much like the nearly 2 million British nationals living in other EU member states. Indeed, Eastern Europeans are narrated as immigrants, whilst Brits living abroad are expats.

Don’t get me wrong, I see nothing wrong with being a migrant; in fact, I’ll happily call myself a migrant in Britain if you are equally happy to do the very same thing and introduce yourself as an immigrant in Spain, or Sweden. This linguistic quandary is not just confined to UK media.

Europe as an alien concept

Whilst Britain’s traditional Euroscepticism has remained the norm, the extent of the anti-EU rhetoric has been made explicit: it includes Western Europe but definitely excludes Eastern Europe.

Britain is clearly narrated as too good for Europe, Eastern Europeans are portrayed as not good enough for Europe. News language has consistently challenged and denied the European credentials of various groups of Eastern Europeans.

From the mid-2000s onwards, Eastern Europeans have been scapegoated and blamed for all kinds of problems: jobs, housing, benefits, crime and anti-social behaviour, despite mounting evidence that they contribute more than they cost the system.

Scapegoating Poles, Slovaks, Romanians and Bulgarians has proved to be an easy task: it did not earn media immediate charges of racism, whilst providing certain political dividends – for the most part, Eastern Europeans are not eligible to vote in general elections.

Daily Mail newspaper, 23 August 2006. A similar headline was repeated in August 2015. Credit – Gideon/Flickr.com

Divide and conquer

Another utterly divisive strategy has been to create various inter-group conflicts. Firstly, media has consistently argued that Eastern Europeans steal British jobs from the white working class, but also from the youngsters who cannot get summer jobs because they have all been taken away.

Secondly, it tried to appeal to British ethnic minorities by postulating that Eastern Europeans are to blame for the persistent problems with unemployment that these communities have been experiencing for decades. Thirdly, with Bulgaria and Romania’s EU accession, news outlets have argued that Bulgarians and Romanians were going to steal Polish jobs.

Impact on the Remain and Leave campaigns

For the most part, media outlets do not report on actual events: they seem to reflect on eventualities, which then they easily convert to political crises.

All this has had an impact on the Remain and Leave campaigns as EU immigration concerns were of key importance to many voters.

The traditional British Euroscepticism, economic conservatism and strong anti-immigrant sentiments, left Remain in a disadvantaged position. They could not appeal to any form of historical or political European identity and for the most part, they had to carefully avoid the question of immigration.

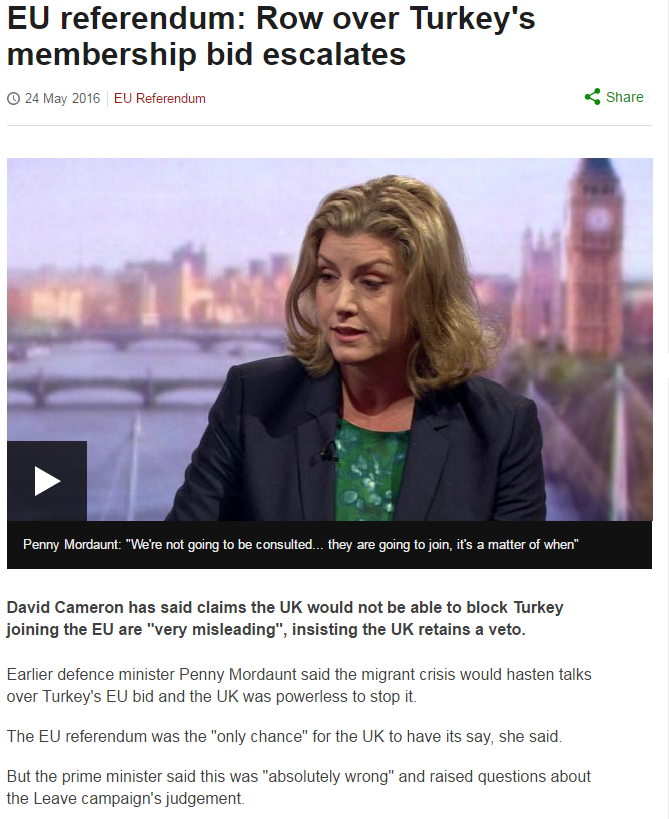

This translated into a decided advantage for Leave, allowing them to use the emotional appeal of reclaiming sovereignty from Brussels, but also to scare people that matters of immigration are only going to get worse because the EU is eager to further expand towards the Western Balkans, perhaps even Turkey.

Clipped from BBC News article, 24 May 2016

And since public discourses have been saturated with scaremongering tactics, many Leave voters needed neither experts, nor evidence. They knew enough about the EU to know it is undemocratic and oppressive.

Data shows that the abundance of expert opinions and academic research are essentially overridden by news language’s assertions that ‘this cannot be right’. The notion that people’s fears and anxieties are self-validating is a contributing factor to a ‘post-truth’ type of discourse.

Concluding remarks

As far as the referendum result is concerned, Brexit is a reality. A very multifaceted reality, in the creation of which news outlets (both tabloids and broadsheets) from across the political spectrum played a fundamentally important role.

The conflation of the concepts of Europe and immigration has had an impact not only on the Remain and Leave campaigns but is also having crucially important policy implications as pressures to reduce EU migration are high on the political agenda and are likely to be a key point during the negotiations.

Currently, millions of EU citizens are living in a constant state of anxiety as to what is going to happen to their acquired rights, as well as their right to family life. There is even speculation that politicians do not want to commit to guaranteeing said rights due to fears of prompting more EU immigration to the UK.

The populist entanglement of EU citizenship and immigration fears is conveniently used by a number of politicians in their own power struggles, including Theresa May’s hint at possible deportations of EU nationals. Here, an important policy question would be ‘who would count as a migrant’?

Since there are no precedents in terms of member states leaving the EU, this question goes beyond media ethics and calls for concrete political commitments that EU nationals in the UK and UK nationals in other EU member states would not be used as ‘bargaining chips’.

Denny Pencheva has previously worked on issues of asylum and irregular migration, EU border control policies, as well as ethno-politics in southeast Europe. Her doctoral research is on Bulgarians and Romanians in British news media (2006 and 2013), and is based on a data set of nearly 1000 news articles.