Tariq Modood, Professor of Sociology, Politics and Public Policy, University of Bristol

The Brexit referendum result was a shock. Especially surprising – given that the whole exercise was as a result of the divisions within the Conservative Party – was the fact that about 30% of those who voted Labour in 2015 voted Leave. It is clear that the Leave vote disproportionately consisted of those without a degree and over the age of 45. Equally over-represented in the Leave vote in England were those who say they are more English than British or only English and not British.

There is some reason to suppose that this new and rising English nationalism is anti-immigration, and even worse – given that England is a highly diverse country – anti-multiculturalist. While it is worrying that the Brexit result seems to have led to an uptick in racial abuse and harassment, there is no reason to suppose that English nationalism and multiculturalism must be opposed to each other.

To many, multiculturalism as a political idea in Britain suffered a body blow in 2001. In the shock of 9/11 terrorism and after race riots in some northern English towns, many forecastthat its days were numbered. If these blows were not fatal, multiculturalism was then surely believed to have been killed off by the 7/7 attacks in London in 2005 and the terrorism and hawkish response to it that followed. But this is far too simplistic.

And today, a multicultural identity among some ethnic minorities could help to create more of a sense of “British identity” among the English.

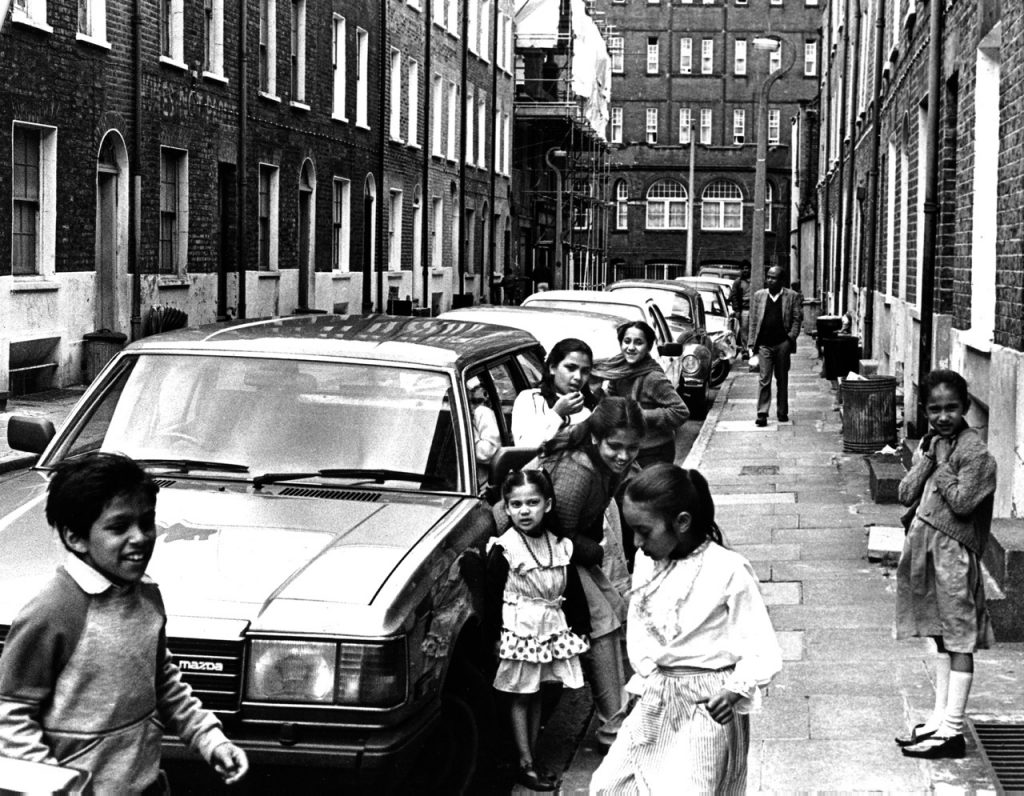

Early second generation Bangladeshis in Whitechapel, 1986. Al Cane/Flickr.com

Multiculturalism in Britain grew out of an initial commitment to racial equality in the 1960s and 1970s into one of positive self-definition for minorities. One of the most significant pivots in this transition was The Satanic Verses affair of 1988-89, following the fatwa against its author Salman Rushdie, which mobilised Muslim identity in a way that ultimately grew to overshadow much other multiculturalist and anti-racist politics.

It is significant that multiculturalism in Britain has long had this bottom-up character, unlike say Canada and Australia, where the federal government has been the key initiator.

The Labour legacy

Nevertheless, anti-racism and multiculturalism in Britain still required governmental support and commitment. The first New Labour term between 1997 and 2001 has probably been the most multiculturalist national government in Britain – or indeed Europe.

Its initiatives included the funding of Muslim and other faith schools, the MacPherson Inquiry into institutional racism in the London Metropolitan Police and the Race Relations (Amendment) Act 2000, which strengthened previous equality legislation. This agenda continued to some extent in the second and third New Labour governments, primarily with the extension of religious equality in law.

Yet, after 2001, and especially after the 2005 London bombings, there were significant departures from the earlier multiculturalism. But it is inaccurate to understand those developments as the end of multiculturalism. They mark its “rebalancing” in order to give due emphasis to what we have in common as well as respect for difference.

At a local level, this consisted of programmes of community cohesion. This was premised on the idea of plural communities but was designed to cultivate interaction and co-operation, both at the micro level of people’s lives and at the level of towns, cities and local government.

At a macro level, it consisted of emphasising national citizenship. Not in an anti-multiculturalist way as in France – where difference is regarded as unrepublican – but as a way of bringing the plurality into a better relationship with its parts. Definitions of Britishness offered under new Labour, for example, in the 2003 Crick report, emphasised that modern Britain was a multi-national, multicultural society, that there were many ways of being British and these were changing. As ethnic minorities became more woven into the life of the country they were redefining what it meant to be British.

The idea that an emphasis on citizenship or Britishness was a substitute for multiculturalism is quite misleading. The 2000 report of the Commission on the Future of Multi-Ethnic Britain – known as the Parekh Report, after its chair the Labour peer, Bhikhu Parekh – made national identity and “re-telling the national story”, central to its understanding of equality, diversity and cohesion. It was the first public document to advocate the idea of citizenship ceremonies, arguing that citizenship and especially the acquisition of citizenship through naturalisation was – in contrast to countries like the USA and Canada – undervalued in Britain.

Questions of Englishness

Yet over the last couple of decades a new set of challenges have become apparent, initially in Scotland but increasingly throughout the UK. In none of the nations of the union does the majority of the population consider themselves British, without also considering themselves English, Welsh, Scottish or Northern Irish first.

Wales beat England, Rugby World Cup 2015. Sum_of_Marc/Flickr.com

The 2011 census is not a detailed study of identity but it is striking that 70% of the people of England ticked the “English” box and the vast majority of them did not also tick the “British” box, even though they were invited to tick more than one. This was much more the case with white people than non-whites, who were more likely to be “British” only or combined with English. Multiculturalism, then, may actually have succeeded in fostering a British national identity among the ethnic minorities.

Multiculturalism in this case, then, offers not only the plea that English national consciousness should be developed in a context of a broad, differentiated British identity. But also, ethnic minorities can be seen as an important bridging group between those who think of themselves as only English, and those who consider themselves English and British.

Paradoxically, a supposedly out-of-date political multiculturalism becomes a source of how to think about not just integration of minorities but about how to conceive of our plural nationality and of how to give expression to dual identities such as English-British. It is no small irony that minority groups who are all too often seen as harbingers of fragmentation could prove to be exemplars of the union.

The minimum I would wish to urge upon a centre-left that is taking English consciousness seriously is that it should not be simply nostalgic and should avoid ethnic nationalism, such as talk of Anglo-Saxonism. More positively, multiculturalism, with its central focus on equal citizenship and diverse identities and on the renewing and reforging of nationality to make it inclusive of contemporary diversity, can help strengthen an appreciation of the emotional charge of belonging together.

Jessica Ennis with the UK flag after winning gold in the heptathlon at the 2012 Summer Olympics. Robbie Dale/Flickr.com

This article is based on a piece originally posted at The Conversation.