Michael Gove and David Laws justified their decision to restructure A-level examinations on the basis of a flawed piece of statistical research, claiming that the absence of AS-level grades for university applicants would not harm the admissions process. Ron Johnston, Richard Harris, Tony Hoare, Kelvyn Jones and David Manley of the School of Geographical Sciences at the University of Bristol have re-examined the data and reached a contrary conclusion: without AS-Levels, late developers – which may include many from educationally-disadvantaged backgrounds – could well have their potential to succeed on a degree course at a prestigious university not recognised.

In 2013 the former UK Education Secretary, Michael Gove, and his Minister of State, David Laws, decided to change the A-Level qualifications taken by English and Welsh post-16 students with academic aspirations. Most of those students currently take GCSE examinations at age 16, in eight or more subjects. In the first post-compulsory year they are examined in four subjects leading to the award of AS-level grades followed, a year later, by exams in three or all four of them for A2 qualifications. The AS and A2 marks are combined to form an A-Level grade.

While A-Level results are the most important basis for university entrance, most students apply before they are known: most offers of places are conditional on their getting specified grades. To decide who should receive offers university admissions officers use the GCSE and AS-Level results to assess students’ potential alongside personal statements, school references and teachers’ assessments of likely A-Level results.

This system will end in 2015. A-Level courses will comprise two-year modules, examined at the end of that period only. AS-Levels are being redesigned for other purposes, not to be taken by students in their chosen A-level subjects. University admissions officers will no longer have quantitative, comparable evidence of students’ post-GCSE performance in subjects central to their university applications.

Admissions officers and others argued that these changes would make identifying those best fitted to study for their chosen degree courses more difficult. To counter that David Laws commissioned in-house research, whose results were claimed to show that, since degree performance could be as accurately predicted from GCSE as from AS-Level results in one student cohort (those graduating in 2011 on three-year degrees), the future absence of AS-Levels would not harm the admissions process. We have challenged the quality of that research elsewhere (see the LSE British Policy and Politics site). Here we further use the Department for Education’s data to show how its results have been misinterpreted.

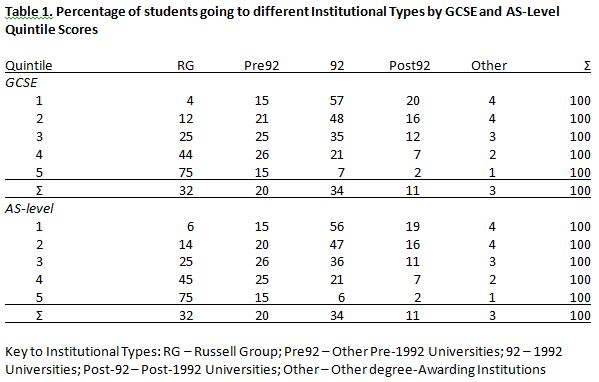

We have placed the UK’s universities into five types according to their average entry requirements:

- The Russell Group;

- All other universities founded pre-1992;

- Universities (the ex-polytechnics) founded in 1992;

- Post-1992 universities; and

- Other degree-awarding institutions.

To identify to which institutions the ‘best-qualified’ students gained admission, the 80,420 for whom we had data on GCSE scores in 2006 and AS-Level scores in 2007 were divided into two sets of five groups (quintiles) according to their performance.

Table 1 shows the expected relationship. Only 4 per cent of students in the lowest GCSE quintile (i.e. the weakest performers) went to Russell Group universities, compared to 75 per cent from the highest quintile, with a very similar difference between the lowest and highest quintiles according to AS-Level results. The common pattern across the table’s two parts apparently sustains the Gove/Laws argument: better-qualified students at either GCSE or AS-Level disproportionately gained places in more prestigious institutions.

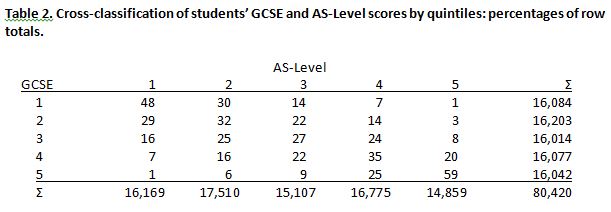

But note that we said or, not and. Implicit in Law’s conclusion is a strong correlation between GCSE and AS-level performance. Perhaps surprisingly, there isn’t: the squared correlation coefficient is only 0.38. Table 2 illustrates this. Only one of the five rows (showing the quintiles at GCSE) has a majority of students according to GCSE scores in the same quintile for AS-Level scores (59 per cent for the highest quintile). Many performed relatively badly at GCSE but much better at AS-level (the ‘late developers’); others did well at GCSE but not at AS-levels a year later (the ‘drifters’). So if admissions officers had only GCSE grades available they may not have offered places to many students whose AS-Level results indicated much greater potential to succeed on a degree course than did their GCSEs; many late developers might have missed out on degree places at prestigious universities.

But note that we said or, not and. Implicit in Law’s conclusion is a strong correlation between GCSE and AS-level performance. Perhaps surprisingly, there isn’t: the squared correlation coefficient is only 0.38. Table 2 illustrates this. Only one of the five rows (showing the quintiles at GCSE) has a majority of students according to GCSE scores in the same quintile for AS-Level scores (59 per cent for the highest quintile). Many performed relatively badly at GCSE but much better at AS-level (the ‘late developers’); others did well at GCSE but not at AS-levels a year later (the ‘drifters’). So if admissions officers had only GCSE grades available they may not have offered places to many students whose AS-Level results indicated much greater potential to succeed on a degree course than did their GCSEs; many late developers might have missed out on degree places at prestigious universities.

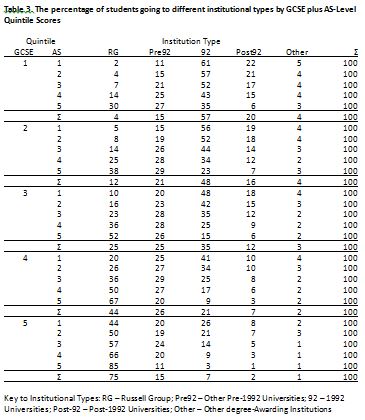

Table 3 elaborates this conclusion, showing the difference in students’ destinations by GCSE and AS-level qualifications combined. For example, just 2 per cent in the lowest quintile for both GCSE and AS-level went to a Russell Group university (the tables’ first row), whereas of those in the lowest GCSE quintile but the highest for AS-Level (the fifth row; the most emphatic group of ‘late developers’) 30 per cent did. In general, students who performed much better at AS-Level relative to GCSE were more likely to obtain a place at an ‘elite university’. Conversely, the poorer students’ performance at AS-level relative to GCSE, the greater the probability that they studied at other institutions.

Table 3 elaborates this conclusion, showing the difference in students’ destinations by GCSE and AS-level qualifications combined. For example, just 2 per cent in the lowest quintile for both GCSE and AS-level went to a Russell Group university (the tables’ first row), whereas of those in the lowest GCSE quintile but the highest for AS-Level (the fifth row; the most emphatic group of ‘late developers’) 30 per cent did. In general, students who performed much better at AS-Level relative to GCSE were more likely to obtain a place at an ‘elite university’. Conversely, the poorer students’ performance at AS-level relative to GCSE, the greater the probability that they studied at other institutions.

The DfE analysts and ministers were wrong in interpreting their (flawed) statistical analysis to conclude that university admissions officers gained no additional value in assessing students’ potential from AS-Level results. This re-analysis suggests the opposite. Many students performed relatively badly at GCSE but their improved performance at AS-Level a year later may have encouraged both them to apply to more prestigious universities and admissions officers to recognise their potential. Without their AS-Level results many ‘late developers’ may not have been given that opportunity; furthermore, many of them may have been from disadvantaged backgrounds and benefited from universities’ widening participation programmes (much favoured by the government).

The DfE analysts and ministers were wrong in interpreting their (flawed) statistical analysis to conclude that university admissions officers gained no additional value in assessing students’ potential from AS-Level results. This re-analysis suggests the opposite. Many students performed relatively badly at GCSE but their improved performance at AS-Level a year later may have encouraged both them to apply to more prestigious universities and admissions officers to recognise their potential. Without their AS-Level results many ‘late developers’ may not have been given that opportunity; furthermore, many of them may have been from disadvantaged backgrounds and benefited from universities’ widening participation programmes (much favoured by the government).

Whatever the political-cum-ideological-cum-educational arguments for restructuring A-Levels the claim that abolishing the intermediate exams at AS-Level would not harm the university admissions process is not sustained by this analysis. Without AS-levels from 2015 on, many ‘late developers’ may be unable to gain entry to the university and degree course of their choice – for which they have the potential to succeed, and universities, including the prestigious ones, would be denied potentially able undergraduates whom they currently recruit in significant numbers.